After The Yom Kippur War

Posted by Crethi Plethi on Fri, November 19, 2010, in Arab-Israeli Conflict, Islamic Countries, Israel, Israel Defense Forces, Israeli–Palestinian Conflict, The Middle East . Fri, Nov 19, 2010

shmuelkatz.com

By Shmuel Katz

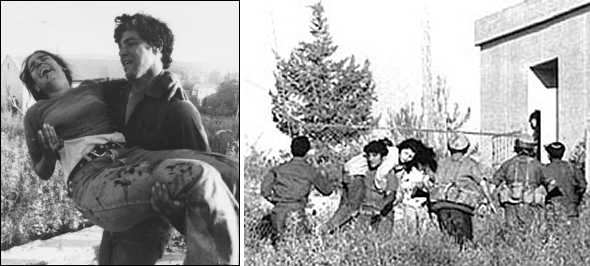

Pictures from the Ma'alot Massacre on May 15, 1974 in Ma'alot, Israel. The Ma'alot massacre was an act of Palestinian terrorism against civilians, in which 22 Israeli high school students, aged 14–16, from Safed were killed by three members of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Before reaching the school, the trio shot and killed two Arab women, a Jewish man, his 7 months pregnant wife, and their 4 year old son, and wounded several others. The three terrorists were killed during the attack by the IDF's elite Sayeret Matkal Special Forces group.

Battleground: Fact and Fantasy in Palestine

After The Yom Kippur War

This article is the ninth chapter from the book “Battleground: Fact and Fantasy in Palestine” written by Shmuel Katz. Yesterday, we published the eighth chapter: Israel’s Function In The Modern World. Tomorrow, we will publish the last chapter. These articles are part of a series of facts, fantasy and myths concerning Israel, Palestinians and the Middle East. For all the chapters of the book, click Here.

About the book: “A fully documented, dramatic history of the events which shaped the Middle East. Every key problem in the Arab-Israel conflict, every decision is carefully analyzed, from the questionable policies of Britain in 1948 to how the Palestinian refugee problem began. The territory won in the war of 1967, and the terrorist war of attrition is discussed.” (From the intro at ShmuelKatz website). To view the entire book online, go to Shmuelkatz.com. To buy the book, go to Afsi.org.

The writing of the original English edition of this book was concluded early in 1972. Thus it was that only in a footnote inserted in the page proofs was there mention of what turned out to be an historic turning point in the Arab war against the Jewish state. In July 1972, the Egyptian President announced that he had asked the Soviet government to withdraw its “advisers” (said to number more than thirty thousand) from Egypt. The reason, he said, was that the Soviets had refused his requests for more sophisticated weapons with which to attack Israel. The Soviet government consequently recalled most of its military personnel from Egypt.

The expulsion was followed by a lengthy period of mutual recrimination. The breach in relations between Egypt and the Soviet Union was warmly welcomed in the West. The euphoria was all the deeper for the fact that the expulsion had followed closely on the heels of an impressive agreement to regulate the relations between the United States and the Soviet Union. One paragraph in this agreement (signed in Moscow on May 29, 1972, by President Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev, Secretary General of the Communist Party of the USSR) laid down that the two governments had a “special responsibility to do everything in their power so that conflicts or situations will not arise which can serve to increase international tensions.”

To the framers of Middle East policy in Washington, ft thus seemed clear in mid-1972 that, partly through the action of Sadat and partly through the Soviet leaders’ readiness for self-restraint, a considerable relaxation of tension was in the offing.

In fact, the expulsion of the Soviet advisers from Egypt, and the noisy cooling of relations between the two countries, was a cleverly conceived, well-coordinated, impeccably executed hoax; and the Soviet government undertaking to honor the relevant clause in the agreement for d6tente was a calculated deception. Both, as it transpired, served as preliminary moves toward the orchestrated, many-pronged Arab aggression against Israel in October 1973.

The motives and ramifications of the Egyptian plan, and the complex tactics of its execution, were subsequently described by Abd al-Satar al-Tawila, then the military correspondent of the Egyptian weekly Rose-al-Yusuf, in a book entitled The Six-Hour War According to a Military Correspondent’s Diary. There he described Sadat’s actions as a “brilliant plan of political camouflage” carried out in a “spectacular manner to mislead the enemy.” He describes how:

The various government agencies spread rumors and stories that were exaggerated, to say the least, about deficiencies, both quantitative and qualitative, regarding the weapons required to begin the battle against Israel, at the very time that the two parties – Egypt and the USSR – had reached agreement concerning the supply of quantities of arms during the second half of 1973 – weapons which, in fact, were beginning to arrive. And there came a time when we saw how the majority of habitues of Egyptian and Arab coffee houses, particularly in Beirut, turned into arms experts and babbled about shortages in this or that type of hardware. And speaking in the jargon of the scientist and the expert, they would say that the Soviets were refusing to supply Egypt with missiles of a certain type and were even cutting off the supply of spare parts in such a manner that our planes, for example, had turned into useless scrap and were unable to fly, not to speak of combating the Phantom and the Mirage. These self-styled arms experts went deeply into the question of offensive and defensive weapons, inventing arbitrary differences between them while – as we shall see in the chapters dealing with the battle – defensive antiaircraft missiles actually played an offensive role during the War of October 6. Moreover, the Egyptian press frequently gave prominence to an inclination [in Cairo] to seek arms in the West. And while it is coned that it Is possible to buy some categories of hardware in the West, to equip a whole army with weapons from the West would mean, simply, that the date of the expected battle remains far off, i.e., until such time as the Egyptian army could be trained in the use of such now hardware….All this talk about armaments and their shortage was intended to create the impression in the ranks of the enemy that one of the reasons why Egypt was incapable of starting war was the absence of high quality weapons….And the whole world was taken by surprise when zero hour arrived. A Pentagon spokesman expressed this surprise when he said:

“They – i.e, the Israelis—did not suspect the presence of such quantities and such categories of Soviet weapons in Egyptian and Syrian hands, in view of the incessantly repeated Arab complaint that the Soviets were refusing to supply these two countries with advanced offensive weapons in sufficient quantities.”

The Egyptian camouflage to deceive the enemy was expanded to include Egyptian-Soviet relations. This was done to such an extent that many among the Arabs themselves cast doubt upon Egyptian-Soviet friendship and its sincerity and allegations were spread concerning Soviet non-support for the Arabs in their struggle. The episode of July 1972, when Egypt decided to make do without Soviet experts, was exploited and many intentionally or unintentionally failed to beer the words of President Sadat and his repeated emphasis that this episode was no more than ‘an interlude with our friend,’ as always happens among friends. Now we already know that one of the reasons for the willingness to make do without the Soviet experts was so that preparations could be made for the beginning of a battle that would bear the character of a 100% Egyptian decision, using 100% Egyptian forces. However, these experts had fulfilled an important task in connection with the network of missiles and other delicate weapons.

The Egyptian deception campaign, moreover, was able to reap considerable benefit from this episode – the willingness to make do without the Soviet experts–because it raised questions about the genuineness of the regimes threats to resort to war since, after all, how would the Egyptian army be able to fight without the presence of thousands of Russian experts, distributed among all the most important weapons sectors of the army so as to train [the army] in their use and even to operate some of this hardware themselves? In addition, the [deception] campaign benefited also from the allegations and suspicions that were spread in the Arab world, as if this [willingness to do without Soviet experts] had been the result of a secret agreement with the U.S. and its friends in the region, whereby a peace arrangement would be prepared in return for the removal of the Soviet military presence. If that was the case why, then, no war was to be expected, nor anything like a war – yet all the time preparations were continuing feverishly to open the battle; and when the war started in fact, there was the additional surprise that unlimited Soviet support was extended both in the international arena and in the area of military equipment. The same Pentagon spokesman, on the morrow of the battle, expressed his opinion about this surprise:

‘We never imagined that the Soviet union would do what it has done after the tough verbal campaigns waged against it in the Arab world, and after the cooling of relations with Cairo following the exodus of the Soviets.’

During a visit to the battlefront on the 7th of October, I heard an ordinary Egyptian soldier give expression to Arab-Soviet friendship in the following simple words:

“Some of you may have believed all this talk – yet our friendship is flourishing – after all, I was being trained to use Soviet-produced anti-tank R.P.G.”

Excerpts from Al-Tawila’s book were published on the first anniversary of the Yom Kippur War in Rose-al-Yusuf – the official organ of the only political party allowed to exist in Egypt. The Journal (of which Al-Tawila was later appointed editor) thus authoritatively told its readers that Al-Tawila. had been encouraged in his work by President Sadat. In fact, Sadat had personally helped him revise the text of the book. Al-Tawila had, moreover, been given access to secret documents. [Rose-d-Yusuf, October 7, 1974]

A year later, President Sadat himself, in an interview on Cairo Radio (October 24, 1975), confirmed Al-Tawila’s version, describing his expulsion of the Soviet advisers as “a strategic cover … a splendid strategic distraction for our going to war.”

The year following July 1972 was employed by the Egyptians in preparing for the surprise attack across the Suez Canal and for its coordination with the parallel attack, by the Syrian forces, on the Golan Heights. The Syrians, incidentally, became direct beneficiaries of the Egyptian-Soviet maneuver: The experts expelled from Egypt were transferred to Syria. Moscow did not do this without the ready consent of the Egyptian government, for Cairo held that “the national interest required the continued presence of Soviet experts in the region.”

In that same period, the Arab states planned the grand strategy – which they had often threatened without being taken seriously – of using their vast oil resources as a political weapon.

Previously, no doubt, it had been difficult to achieve united action even among the oilproducing states, and certainly not with the non-Arab oil producers. In 1970 however, the oil-producing states, having united in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), had already begun a process, albeit comparatively moderate, of raising prices. Now, at some point in 1973, they had come to a radical decision to execute a sudden and steep increase. The Organization of Arab Oil Producers (OAPEC) decided at the same time to proclaim an embargo, to coincide with the war they were preparing against Israel. This embargo would deny oil to the whole of the Western world in order to extort from them support, in bringing Israel to her knees. Overnight the countries of Europe and Japan, heavily dependent on Middle East off, would be reduced to the status of suppliants.

The timing of the OPEC announcement – on October 16, 1973, the eleventh day of the Yom Kippur War – of a drastic rise in oil prices to coincide with the of the embargo was for the Arabs a happy means of making it appear, even if briefly, that Israel was at the root of the difficulties of the West. The next day, the Arab oil exporters published their threat

“to reduce oil production by not less than 5 percent of the September level of output in each Arab oil exporting counties, with a similar reduction to be applied each successive month until such time as total evacuation of Israeli forces from all Arab territory occupied during the June 1967 war is completed and the legal rights of the Palestinian people are restored.”

This remained an unfulfilled threat. The embargo was lifted in March 1974, and indeed its precise scope, while it lasted, has remained a matter of controversy. The atmosphere of emergency and indeed near-panic it induced was exaggerated, as were the intensely gloomy prophecies about its effect on the Western economies. Its impact on the Arab-Israeli war itself also was minor, but it could have been serious because of the supine accommodation of most of the governments of Europe to the threats of the Arabs.

The war could have been over in a few days. A relaxation of alertness throughout the Israeli Army, lowered standards of discipline and arms maintenance compounded by political misjudgment of Arab and Soviet intentions, found Israel at the opening of the war in a position of tactical inferiority, unable to prevent or even effectively counter the successful exploitation by Egyptians and Syrians of the element of surprise. Caught off balance, some of the Israeli commanders in the field blundered in the early stages. The result was a substantial number of Israeli casualties and spectacular Arab successes. The Egyptians captured a strip of territory on the East Bank of the Suez Canal and the Syrians a generous portion of the Golan Heights. Only a display of outstanding bravery in the Israeli ranks on both fronts prevented a military disaster.

Yet the Israeli Army not only succeeded in extricating itself from the critical situation thus created, but tamed the tables completely. By the tenth day of the war, all of the Golan Heights had been regained, and Israeli forces had in addition occupied a substantial area in Syria, where they posed a direct threat to Damascus. In the south, although the Egyptian forces – the Second and Third Armies – held their positions east of the Canal, a brilliant break through their center and across the Canal had been followed by the occupation of a much larger salient inside Egypt proper. There, indeed, the road to Cairo was open. The Third Army trapped and encircled west of the Canal, was doomed. It was precisely at this point that political pressure from the Nixon administration, which the Israeli government found irresistible, forced them to agree to a ceasefire.

As the war progressed, the moral weakness of Weston Europe was pitiably exposed. One reason for the precarious state in which the Israeli forces found themselves after the initial Arab onslaught was the decision Israeli government, even when they had realized that the attack was imminent, not to deprive the Arabs of any of the benefits of surprise. They had refrained purposely from taking preemptive action. Moreover, they purposely delayed even the full call-up Reserves – the main body of the Israeli Army.

Purpose of this restraint was to prevent any misconception, or pretended misconception, about the identity of the aggressors. The Israeli government wished to prevent a repetition of the ludicrous charges of aggression laid at Israel’s door in 1967, when she took preemptive action in the face of the belligerent closing of the Straits of Tiran and the massing of the Egyptian and Syrian forces for the declared purpose of Israel’s annihilation. Now, the government’s restraint turned out to be irrelevant, ineffective, and costly beyond measure or repair. They did not reckon with the realities of international motivations. When the United States government applied to the governments of Europe to allow her planes, bringing supplies to the battered victim of aggression, to land on their airfields for refuelling, they refused for fear of offending the Arabs. Fortunately, the United States had rights, secured by treaty, to land her planes in the Portuguese colony in the Azores. The Portuguese agreed to respect these rights, and the desired weight and speed of supply to Israel in the latter phase of the war were thus ensured. The stark realities of European moral flabbiness were compounded by the applied power of Arab oil. The embargo reduced presumably proud governments in Europe to whimpering impotence. “Nous pesons peu” (we count for little), cried Michel Jobert, the French Foreign Minister, in the National Assembly; and the West German Foreign Minister subsequently explained that his government was “aware of the limits of her influence.”

The central effect of the oil boycott, as gradually transpired after the event, was psychological. It diverted the attention of frightened populations away from the concomitant steep rise in price (fourfold in less than three months). Its long-range effect was as a threat, a demonstration of the seemingly irresistible power that resides potentially in the hands of the Arab oil states. With the passage of time, however, the organization of oil reserves, the provisions made for mutual aid and cooperation among the consumer states, the discovery of new oil sources, and the development of alternative fuels, suggest that a future embargo will be far more difficult to apply effectively.

The real change – palpable, swift, and far-reaching in the very fabric of international relations – that developed after mid-October 1973 derives from the rise in the price of oil. Its implications and consequences transformed the potential of the Arab states into unprecedented economic power. They have transmuted this power into political terms and have applied it in every possible direction with a ruthlessness sometimes sophisticated, sometimes openly brutal. Its weight has been directed to the consummation of the central short term purposes of the Arabs: the annihilation of Israel. But in counterpoint to that purpose, there wells up, unmistakably, the theme of Arabdom as a world power, avenging itself, moreover, on the hitherto supercilious and allegedly exploitative West. Not only fabulous wealth, but the idea of the peoples of the Christian West – Britons, Frenchmen, Germans, and even Americans – hungry for oil and deals and dollars, abasing themselves before Moslem overlords, has fired Arab imagination with the vision of a new golden age of domination in the world.

By a combination of circumstances, the Arabs have derived considerable aid and comfort from the sorrows of the United States – the trauma of Vietnam and the agony of Watergate – as well as from the policy ofWashington toward the Soviet Union.

Early in 1976, with the debacle for the West following the successful intervention in the Angolan Civil War by Cuban troops sponsored and armed by the Soviet Union, it was very widely agreed in the United States that the declared policy of detente, pursued for several years, had been a grotesque failure derived, as its critics had long maintained, from a disregard of, or an inability to understand the purpose of, the priorities, the thought process, and the mode of operation of the Soviet leaders. Far from weaning them away from dreams of world domination and deepening their interest in noncompetitive ideological coexistence, the policy of detente had proved to be a powerful vehicle for furthering their plans for expansion and their dream of Communist predominance throughout the world.

The failure was measurable, for detente was not a vague generalization. It was codified in the formal Nixon-Brezhnev agreement in Moscow in May 1972. In addition to the undertaking to do everything in their power so that conflicts or situations would not rise which would serve to increase international tensions they also promised – among the twelve principles agreed upon to prevent the development of situations capable of causing a dangerous exacerbation of their relations and to do their, utmost to avoid military confrontations.

This agreement, as far as it affected the conflict between Israel and the Arabs, effectively helped to lull Jerusalem (and Washington) into a false sense of security. The Soviet government refrained from carrying out those of its provisions which might conceivably have prevented war. The secret delivery, behind the heavy smoke screen of “a quarrel” with Egypt, of large quantities of arms into Egypt as well as Syria was not precisely a means of preventing “conflicts or, situations … which would serve to increase international tensions.” Nor did they warn the United States, as they were pledged to do, when they knew the Arab offensive was imminent. They did indeed send planes to evacuate Soviet families from both Egypt and Syria two days before the war broke out, but American Intelligence believed this was part of the “quarrel.” Having extended the aid designed to give both countries the maximum advantage in opening the war, the Soviets executed throughout its progress what they themselves described as an “uninterrupted flow by sea and air of Soviet arms and ammunition to Egypt and Syria.”

They went further: They called on the other Arab states to join in the war. In a message to President Boumedienne of Algeria on October 9, and to the heads of other Arab states the next day, Brezhnev wrote:

Today more than ever Arab brotherly solidarity must play its decisive role. Syria and Egypt must not remain alone in their fight against a perfidious enemy.

Sponsoring aggression in the Middle East was only one facet of the dynamic policy of the Soviet leaders. The USSR continued to build up her military power in every field with single-minded intensity and with a high efficiency detectable in no other sphere of her economic endeavor. Her military manpower grew (by 1975) to 4.4 million, more than twice the size of the United States establishment. In every category of military production except helicopters, she drew ahead of the United States. In ground-forces equipment, the ratio rose to about six to one. In the air, still qualitatively inferior, her production rates in fighter aircraft in 1975 exceeded those of the United States Air Force by a factor of four.

Nor did the detente agreement inhibit or slow down the uninterrupted expansion of the Soviet Navy – the most significant and the most spectacular phenomenon in the changing balance of international relationships. The progress was summed up succinctly by James R. Schlesinger, former United States Secretary of Defense:

“It has become a formidable blue-water navy challenging that of the United States.”

Moreover, taking advantage of some clauses in the first Strategic Arms Limitation Agreement (SALT 1) of 1972, and by ignoring other clauses, the Soviet Union attained superiority in the field of nuclear missiles. Not least significant, in contravention of that agreement, she built up an anti-nuclear CM defense system, thus creating for herself the essential prerequisite of a nuclear war-winning capability – which the agreement was specifically designed to deny to both sides.

All the while, the United States was not only decreasing her military expenditures (by about 3 percent per annum), but, by means of huge supplies of wheat and consumer commodities, helping the Soviet Union to overcome her continuing food shortage without having to reduce her military build-up, and, together with other Western nations, especially France and Germany, helping her develop an otherwise unattainable technological capacity.

What is no less important, the chief architect of American foreign policy, Dr. Henry Kissinger, consistently brushed aside all criticism of this policy as well as the pertinent questions and doubts and fears aroused by Soviet behavior under detente. He rushed to the defense of the Soviet Union even on its behavior in the Yom Kippur War. He announced at its – height that the Russians were “less provocative, less incendiary, and less geared to military threats, than they were in the Six Day War in 1967.” Soviet behavior so far could not, he said, be judged irresponsible.

But the breakthrough with the most far-reaching immediate impact achieved by the Soviet Union was in the reopening of the Suez Canal. In prospect of that reopening, and parallel to the growth of her navy, the Soviet Union expanded its network of bases and base facilities in the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf Zone. By the time the Canal was reopened – in June 1975 – Russia had established no fewer than four bases covering its immediate approaches. In addition to the three in the People’s Republic of South Yemen, she had built the largest of her bases outside the Soviet Union itself, at Berbera in Somalia.

The opening of the Canal released the coiled spring of Soviet power. Moscow was now not only physically equipped, but was freed from her logistic shackles for the pursuit of a policy of intervention and expansion. She was now complete mistress of her own strength, free to deploy her resources as she wished. The Canal, hitherto an obstacle, was now transformed into an instrument of Soviet strategy. The Soviet leaders quickly sensed the overwhelming central phenomenon in the process by which the reopening of the Canal had been achieved: the strange complaisance of the United States. For whether through extreme political myopia, on a deep fatalism, or a failure of will, or all of these, the fact remained that the great prize – the opening of the door to supremacy in the Indian Ocean, in the Persian Gulf thus to the oil sources of the Middle East and into the African continent; the renewal of full exploitation both of the Soviet Union’s naval strength and of her geographical proximity to the area of prospective intervention; the ending of the frustrations of bottled-up Soviet power and repressed Soviet ambitions – this great many – colored prize had been presented to her by her main geopolitical and ideological rival. The reopening of the Canal was achieved by the energetic initiative and effort of the American Secretary of State. Still more incredibly, it was presented to the Soviet Union incidentally, as though absentmindedly, in an apparently unrelated context, and thus did not require any payment, or concession, or undertaking, or even vote of thanks. Moreover, it was displayed to the world, and accepted in the West, as part of a diplomatic victory for America.

How had this situation, yet another compound of Kafka and Orwell, come about?

Immediately after his assumption of office as Secretary of State, Dr. Henry Kissinger called in the ambassadors to the UN of thirteen Arab states and told them that he understood the Arab states could not resign themselves to a perpetuation of the status quo in the Middle East. He promised them that the United States would work for a solution to the problem.

Eleven days later, Egypt and Syria attacked Israel. Not all the resources of United States and Israeli Intelligence had been adequate to foresee the attack. When the Israeli Army, after its initial were and nearly fatal setback, began turning the tables, and while the Soviet Union was operating its new, massive supply train, airborne and seaborne, of supplies to Egypt and Syria, the losses the Israeli Army bad suffered threatened a shortage of essential materiel. There occurred then a never officially explained delay, lasting eight days, in the shipping to Israel of promised supplies by the United States. In reply to the daily agitated appeals by the Israeli Ambassador, the American Secretary of State claimed that it was the Defense Department that was holding up the supplies. In fact, the Defense Department was acting according to the directions of the State Department. What the Secretary of State omitted to explain to the Israeli Ambassador was that (as he had explained to his colleague, the Chief of U.S. Naval Operations, Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt, Jr.) it was his intention to see Israel “bleed just enough to soften it up for the post-war diplomacy he was planning.”

After two weeks of war Israel, according to all responsible military analysts, could without difficulty have broken Egypt’s power of aggression and inflicted a no less crushing defeat on the Syrians, thus ensuring for herself a long period of peace and for the Western nations a freezing of Soviet advances and ambitions south and east of Suez. At precisely this point, the American Secretary of State, having reached agreement with the Soviet government, conveyed to the Israeli government from Moscow the preemptory “advice” that they accept an immediate ceasefire.

The hopes the Israeli government had had of exploiting the overwhelming military advantage it had gained at terrible cost crumpled under the pressure and threats of the Secretary of State. Yet the Egyptian Third Army, about one half the force that had crossed the Canal, was still encircled and its supplies completely cut off. Israel had only to maintain the standstill in order to ensure its surrender and the return of her own army to the southern stretch of the East Bank of the Suez Canal. The Americans now cajoled the Israeli government into lifting the siege.

In two other decisive stages, the Secretary of State dictated the conversion of Israeli victory into defeat. These were the so-called “disengagement agreements.” In an entangled situation, with elements of each side behind the enemy lines, the obvious and logical way to effect disengagement was, of course, to disengage: The Israeli forces would withdraw eastward across the Canal from the deep salient they had occupied in Egypt proper, while the Egyptian forces would withdraw westward across the Canal from the strip they had occupied on the Sinai bank of the Canal, and the Canal would be the separating line. This was in fact proposed by the Israeli Prime Minister, but it did not accord with the vision of the American Secretary of State. Under his intense pressure, only the Israelis withdrew. By the first disengagement agreement (January 1974), the new Israeli line was established on the Mitla and Gidi Passes, some fifteen kilometers into the Sinai Desert.

In the second disengagement agreement (September 1975), the Israeli government surrendered these strategically important passes as well as her hold on the Red Sea coast and the Abu-Rodeis complex of oilfields–her only independent source of oil, providing her with some 60 percent of her total requirements.

Egypt’s overall substantive contribution to the agreements was to accept the gifts, to promise not to attack Israel for a period of three years, and to reopen the Canal. The reopening was solemnly paraded (though not by the Egyptians) as “a step towards peace,” as a great boon confirmed on the countries of Europe (who could, after all, also use the Canal), and as a concession to Israel.

The fanfare accompanying Dr. Kissinger’s diplomacy drowned the many voices in Israel and elsewhere that cried out against handing over to the Arabs and to the Soviets (hovering, modest and relaxed, in the background) such massive strategic advantages, to the peril both of Israel and of the West.

A parallel if less spectacular development was brought about by American pressure on the Syrian front. There a disengagement agreement provided for a unilateral Israeli withdrawal not only from the deep salient threatening Damascus in Syria proper, but also from a strip of the Golan Heights captured in the Six Day War. Syria gave the same quid pro quo as Egypt. She accepted the gifts. She also agreed to accept a loan from the United States.

The actions of, the American Secretary of State made a sharp, clear pattern. The withholding of arms from Israel during the war, the imposition of the ceasefire saving both Egypt and Syria from crushing defeat and then the step-by-step transformation of Israeli victory into defeat, were naked demonstrations of the fulfillment of his promise to the Arab ambassadors on the eve of the war. Nor in fact did he conceal his purpose. Immediately after the war, he hastened to condone Arab aggression. “the conditions that produced this war,” he said, “were clearly intolerable to the Arab nations.” Two weeks later, during a visit to Peking, he made the ominous forecast that if what he described as the forthcoming “peace” negotiations were successful, Israel would face grave problems. She would have to withdraw from territories and would then need “guarantees” — American or international for her “security.” The boundaries he had in mind for Israel obviously would be inadequate for that security, even from his point of view. Subsequent declarations in the same vein left no doubt that he intended to bring about an Israeli surrender of approximately all the territory she had gained in repelling the Arab aggression of 1967: that is, the first stage of the Arab goal.

These declarations were underlined by President Sadat’s repeated assurances, from February 1974 onward, that he recognized a “significant change” in American policy, and of his personal trust in the man he called his “brother Henry,” and by his relaxed assertions, both to his people and to foreign interlocutors, of confidence that the Arab purpose would be achieved. This confidence was echoed by leaders in other Arab, countries.

It was evident, however, that the Secretary of State had imposed a condition of his own: that the Arab leaders must reconcile themselves to the fact that total Israeli withdrawal could not be achieved all at once. It would be essential to apply a “salami” policy–to be graced, however, by the more elegant nomenclature of “step-by-step diplomacy towards peace.”

The American State Department proclaimed the disengagement agreements as great diplomatic victories. Egypt gave no substantive quid pro quo to Israel, but the United States itself was to derive benefit of the utmost importance: Soviet influence in Egypt was to be replaced by American influence. Again there developed a campaign of criticism and recrimination by Egypt against the Soviet Union. The grounds were, again, the non-supply, or the inadequate supply, of sophisticated weapons. The similarity of this campaign to that which preceded the Yom Kippur War strongly suggests a repetition of the hoax of 1972-73.

It would be a very rational hoax. The reopening of the Suez Canal greatly diminished the importance of Egypt in the Soviet Union’s further penetration of Africa, the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf, and Red Sea zones. As for the naval facilities located on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast, these are feasibly replaceable certainly by Syria at Latakia, perhaps also by Libya. If Soviet imperial expansion can be pursued behind a waterfall of American self-congratulation on having “driven” the Russians out of Egypt, and if Washington can thereby flourish a story of success to brighten an otherwise gloomy record in foreign policy, thus bolstering up the detente policy that has brought such tremendous benefits to the Soviet Union, then another publicized quarrel with Egypt is a low price to pay. In fact, the noisier and more realistic, the better. During such a quarrel, Egypt should indeed not have to suffer a shortage of the proper types of arms, which the United States might not be able to supply. This remained a Soviet interest – a hedge against a possible future return of Israeli forces to the Canal. The problem of clandestine supply had, however, been solved once before and could be solved again.

Accommodation in the West to the desires of the oil-rich and population-rich Arab states was strongly in evidence before the Yom Kippur War. In the war’s aftermath, it became a dominant feature of policy in nearly all the Western nations. Perhaps they had recovered from the trauma of the oil embargo, but they were now enmeshed in the revolutionary, even cataclysmic, consequences of the four-fold, and later fivefold, rise in off prices. The unprecedented drain on their financial resources threatened, in one degree or another, to disrupt their economies. Indeed, present chaos, or near-chaos, and a lurid apocalyptic vision of the future, dominated the thinking of a generally nerve wracked and bewildered leadership in the Western nations.

The precise impact of the transfer of gigantic financial resources from the West into the grasp of a handful of oil-producing states will not soon be measured. At first, fear predominated that the oil states, especially the Arabs with their political motivations, and because of their small populations and large surpluses unproductive in their own countries — such as Saudi Arabia, Libya, Kuwait – would buy up large segments of the economy of the West and thereby exert an unwelcome influence on public affairs. In the United States, in Western Europe, in Japan, there was in fact a considerable buying up of real estate and “buying into” banking, industrial, and commercial concerns, including American oil companies. The cultural field was not neglected: Publishing, firms were bought into, and Arab and Islamic-oriented faculties were established at American universities.

Whether justifiably or not, the fears were soon submerged in a flood of Western initiative. Large doses of antidote were available, calculated to bring back at least some of the dollars that had flowed out. Thus, while potential buyers and investors from the Arab oil countries were to be seen in large numbers in the cities of the West, equally ubiquitous have become the salesmen of Western commerce and industry, real estate, and banking, looking for business in the capitals of the Arab states. “Recycling the petrodollars” has become a national sport in the Western nations. Whatever the ultimate size and weight of the financial and sociological implications and consequences of the two-way process, its immediate political impact on the conflict over Palestine has been very great indeed.

Needless to say, the Arabs have exploited the West’s pursuit of petrodollars in the immediate sphere of finance and business. They have intensified and extended the “secondary” boycott against Israel: the blacklisting of non-Israeli firms doing business with her. More spectacularly, they have become more openly insistent in trying to compel Western firms to collaborate in the boycott of Jews by cutting out Jewish suppliers, Jewish associates, and Jewish employers in any transaction with an Arab country. Much of this pressure is not publicized. From time to time, however, an especially prickly case comes to public notice. Considerable publicity thus attended the pressure to exclude two famous Jewish-owned banks in Britain – N. M. Rothschild & Sons and S. G. Warburg – from an international loan issue launched by a London bank for a Japanese company. There was a public outcry, but it did not affect the outcome, The two banks remained excluded.

Many firms refused to become parties to such Nazitype racism, but many others succumbed. A survey carried out in the United States by the New York Anti-Defamation League led to the conclusion that there was in fact a “widespread willingness” on the part of American businessmen and institutions to conform to the boycott.

It is the political attitudes of most Western governments to the conflict over Palestine that have been most influenced by the changed international economic relationships. The possession of oil and of great purchasing power has now become the prime if not the only operative criterion of right and justice–certainly the criterion for legitimacy. Thus, with one notable exception, there has hardly been an anti-Israel resolution among the mass of such resolutions sponsored by the Arabs at the United Nations, however outrageous morally, however baseless factually, however, infantile intellectually, that has been opposed outright by the civilized Western states. On the whole they abstain. They do not allow what they know of the facts of the dispute to cloud their judgment. They pretend to be unaware of the Arabs’ imperialist appetite; of their annihilative purpose toward Israel; of the historic, political, and moral relationship to the land which over many centuries their whole culture has known as the land of Israel. It has thus, broadly speaking, become the comfortable common cause among these civilized Western states that Israel should surrender territory down to the old Armistice lines of 1949 – from which the Arabs prepared in 1967 to launch the “final attack” on her.

The Arabs’ most spectacular success after 1973, however, has been to turn the international community into accomplices – albeit, passive – in legitimizing the instrument designed to destroy what would remain of Israel after that withdrawal.

For the achievement of such complicity by Western nations, accepted values, of culture and civilization had to be thrown overboard. The international institutions within the United Nations that were established to promote, to disseminate, and to perpetuate those values had to be subverted and prostituted, and even the formal regulations and norms protecting them in the Charter of the United Nations had to be abused and undermined. The Arab states, however, encountered little resistance.

Thus, in November 1974, a year after the Yom Kippur War, the world was treated to the spectacle of Yasser Arafat, the leader of the Arab terrorists, a revolver showing at his hip, addressing amid noisy acclaim the Assembly of the United Nations. Fourteen months later a representative of his organization was seated as a participant – lacking only the right to vote – in a meeting of the Security Council.

On the Arab side, these developments were neither sudden nor the fruit of spasmodic opportunism. They were well and long thought out. They were the result of a clear change in tactics by the Arab states after the oil and petrodollar weapon had proved its potency. Before the war, the pattern of their propaganda, their pressures, and their strategy had been governed by the logic of geography: first the “erasure of the consequences of the 1967 War” – that is, Israeli withdrawal to the 1949 Armistic lines – and then the concentrated physical attack on the attenuated Israel by a sea of Arabs, all wearing “Palestinian” uniforms and fighting for the “restoration of their legitimate rights”: that is, the elimination of Israel.

When the American pressure began to bear fruits, when Israel had physically given up part of the gains of 1967, and the further consummation of the Arabs’ objective seemed to them no longer in doubt, they changed the order of priorities. It became possible at owe – without waiting for the gradual process of Israeli withdrawal – to establish the diplomatic basis for the most radical part of their dream: the creation, in the public consciousness, of the “Palestine State” on the ruins of Israel. To this end, considerable diplomatic activity was required – for coordination among the Arab states themselves, for coordination with the Soviet bloc and with the submissive African states–to test the reactions of the Western states, the degree of passivity with which they would swallow the project.

The terrorist organizations had certainly come – or been brought – a long way since their crushing defeat in Jordan. The Arab states had then acted swiftly to ensure the speedy rehabilitation of their protégés. Some latitude, to be sure, had to be given them in executing at least some symbolic revenge on Jordan. But the promise and the arrangements for their continued existence, for quartering them (mainly in Lebanon), for financing their arms, their training and their propaganda, were necessarily accompanied by the condition that they concentrate their main effort against the Israeli enemy.

Symbolic revenge found expression in the appearance of a new organization that called itself Black September, in memory of the events in Jordan in 1970. The first operation claimed by the organization was appropriately a blow against Jordan. On November 28, 1971, King Hussein’s Prime Minister, Wasfi el Tal, was shot down in a Cairo street. The four assailants did not resist arrest. They were not put on trial but were subsequently simply released by Egyptian authorities.

In fact, Black September was not a new organization at all. The nature of its operations, the new dimension of brutality which became its hallmark, made it convenient for Fatah and its leader to avoid identification with it.

Most of its activities in the next two years were carried out at a distance from Israel. They consisted mainly of efforts to attack civilian airplanes on the ground at Rome or Athens airports or by means of stratagems. For example, a gift, chivalrously given to an unsuspecting girlfriend flying on an El Al plane to Israel, contained a time-bomb. Most dramatic of their exploits were the attacks on unsuspecting groups of people, related or unrelated to Israel, in airplanes or elsewhere, and holding them as hostages against the satisfaction of various demands. Usually these included the release of prisoners, jailed in Israel or other countries as well as money and safe conduct to one of the Arab states. Arab terrorism now became also part of an international phenomenon. Liason and mutual cooperation was widely reported with terrorist groups in Italy, Germany, Ireland, and elsewhere.

Thus, the one major act of terror carried out on Israel itself was the 1972 attack by three Japanese terrorists at Lod Airport. Landing from a plane on March 25, they took up positions in the airport’s arrivals hall and machine-gunned their fellow passengers. They killed twenty seven people, including twenty pilgrims from Puerto Rico who had come to celebrate Easter in the Holy Land. Eighty others were wounded.

Black September’s own tour de force that year was performed in Munich, Germany. There, in September, they murdered eleven Israeli athletes who had come to participate in the 1972 Olympic Games. They had first trapped them, unguarded and unarmed as they were, in their sleeping quarters.

As though to flaunt its special tactics of warfare, Black September carried out an act of equal wantonness six months later. This time, for reasons unexplained, the chosen field of battle was inside Arab territory: the Saudi Arabian Embassy in Khartomn, capital of Sudan, where the ambassador was giving a party. The attackers had no difficulty getting in, nor in subduing five unarmed diplomats and taking them captive into another part of the building. They soon released the two Arabs among them: the host, and a Jordanian. Many hours of negotiations then followed with Sudanese authorities. To this end, the terrorists reported and received orders by radio communication with Beirut. Then the three remaining captives – a Belgian and two Americans – were shot dead in the chain to which they had been tied. The killers were arrested.

There were perhaps some valid inter-Arab reasons for the operation, but the Sudanese authorities, in their anger, now publicly dispelled whatever doubt may have existed about the authenticity of Black September. They announced and published documents proving that Black September was indeed none other than Fatah, and that the organizer of the killing in Khartoum was in fact the local official representative of Fatah. Sudan’s Vice President later announced that the order to kill had come by code, on the radio from Fatah headquarters in Beirut. Later, unofficial reports added that the order had been given personally by Yasser Arafat. Arafat now admitted that “there are some Fatah members in Black September.” A member of Fatah, captured in Jordan, revealed that the operative leader of Black September was Arafat’s deputy, Salah Halef, known as Abu Ayad.

The massacre at Munich had evoked expressions of horror throughout the Western world. The terrorists knew no bounds after the gruesome event in Khartoum. The American government demanded that Sudan deal with the murderers with due severity, and newspapers throughout the world called for countermeasures against this new barbarity. The New York Times expressed the view that it was “inconceivable” that Black September should be allowed to exist. Then sentiments failed, or pretended to fail, to understand the realities.

But by the time the Yom Kippur War broke out, nobody could continue to feign ignorance of the fact that Black September was Fatah, just as Fatah and its sister organizations were a completely integrated arm of the Arab states. There, each new operation was greeted with public approval and enthusiasm. The only Arab government that officially announced its active role in the worldwide operation of Black September was Libya. In fact, all the requirements of the terrorists were placed at their disposal by one or another of the Arab states as required, and the embassies of the Arab states, in carefree disregard of all international agreements and procedures, became bases for terrorist activities.

All Arab perpetrators of terrorist acts found sanctuary, when they needed it, in the Arab states (except Jordan). In some cases, they were given public receptions as heroes; in others, they were quickly removed from the public eye and returned to their base. Sudan had reacted to the murder of the diplomats and had responded to the terror-stricken reactions in the United States by emphatic, unequivocal, and repeated undertakings to punish the murderers. But in fact, after a while, the Sudanese government packed the murderers off to Egypt where Sadat freed them without fuss.

The Yom Kippur War presented Yasser Arafat and his organization with a great opportunity. Suddenly the Israeli Army was engaged heavily on two fronts and was plunged into dire difficulties. Large numbers of Israeli Reserve soldiers were being moved to the fronts, and civilian life in Israel was suddenly in a state of upheaval. Here was a favorable, even ideal, set of circumstances for major action – to set up a third front: to divert Israeli forces to the “Fatah front” on the Lebanese border, to attack Israeli Army installations and forces behind the lines in Judea and Samaria and indeed on the roads and in the cities of Israel. This is what might have been expected by those throughout the world who, on radio and television and in the newspapers, absorbed the daily ration of information on the size and prowess of the Palestinians. Nothing of the sort happened, however. Neither Fatah nor any of its sister organizations played any noticeable part in do Yom Kippur War.

It was only after the war, in the gloom and atmosphere of defeat that had been induced in Israel by the revelation of the unwarranted shortcomings and blunders at its opening, by its heavy toll of casualties, and by the crashing cruelty of American pressure at its conclusion, that the Arab terrorist organizations mounted a new series of operations. Now they no longer used the camouflage of Black September, but explicitly that of their collective identity – ”Palestine Liberation Organization”–or of one of its constituent bodies. Now, indeed, they operated, mostly from their bases in Lebanon, against and inside Israel itself.

The onslaught began in the spring of 1974. During that year, in addition to a number of smaller operations – such as the flinging (by two non-Arab allies from abroad) of hand grenades from the balcony of a Tel Aviv theater into the crowd below – they launched a dozen major attacks. Some were nipped in the bud; a number succeeded. Several places in northern Israel were thus added to their annals of Arab achievement, gaining a somber fame throughout the world: Nahariyah, Beit She’an, Shamir. The pattern of these attacks was exemplified by the events at Kiryat Sh’moneh and Ma’alot.

Kiryat Sh’moneh is a village in the mountains of Galilee close to the Lebanese border. It was there that the PLO opened its offensive. Shortly before dawn on April 11, 1974, three of its members, two Syrians and one Iraqi, went into an empty schoolhouse on the outskirts and, as dawn broke, fired into the street. Upon the arrival of Israeli soldiers who returned their fire, they found a way out of the building, crossed a street, and went, into an apartment building. They entered an apartment and, using Kalashnikov automatic rifles, shot Mrs. Esther Cohen, age forty, her seventeen-year-old son David, and her daughter, Shula, age fourteen. They then went quickly to other apartments in the building. Some they entered, firing at the occupants, most of whom were eating breakfast; into others they simply threw hand grenades. In the noise and confusion of the next ten minutes, they made their way into the adjacent building to continue their attack. By the time the Israeli soldiers caught up with them and shot them, they had killed six more Israelis between the ages of two-and-a half and eleven as well as eight civilian adults. Sixteen men, women and children were wounded but survived, and Israeli soldiers were killed.

Even more spectacular was the operation a month later at Ma’alot, a village somewhat farther from, the Lebanese border. Here the attackers arrived earlier in the day, at 3:00 am., when everybody was asleep. They knocked at the door of one apartment and one of them called out in Hebrew: “Police! There are terrorists around!” When the door was opened, the terrorists entered and shot Yosef Cohen, his wife Fortuna, and their four-year-old son Eli. They also shot the daughter, five-year-old Beah, but she survived. From the Cohen apartment, the terrorists went across the road, again to a school. But this school was not empty. Housed in it were more than one hundred high-school pupils on a hiking tour from Safed, resting for the night. The attackers woke the sleeping children and, wielding their Kalashnikovs, herded them, together with their teachers, into the hallway. Some of the children and one of the teachers succeeded in slipping away and escaped by jumping out of a window. The rest were held for fourteen hours. When Israeli soldiers rushed the building, the Arabs fired into the crowd of children, hitting eightyfour of them. Twenty were either killed instantly or later died of their injuries.

These operations were hailed with enthusiasm by the communications media in all the Arab states. They were described later that year by Farouk El Kadoumi leader of the Fatah delegation to the Conference of Foreign Ministers of the Arab States at Rabat, as “great operation of military heroism.”

The cries of horror that resounded throughout the West did not inhibit the great diplomatic offensive maintained by the Arab states throughout that year. Its first stage was brought to a successful conclusion by the end of 1974. Arafat himself was active in the offensive, moving from one Arab capital to another, and twice visiting Moscow in April and July. He had also had an earlier meeting in March with the Soviet Foreign Minister in Cairo, after which Mr. Gromyko sounded the keynote of the diplomatic offensive: He announced that the Soviet Union regarded the PLO as the sole representative of the Palestinians.

It was on October 14, 1974, that the concentrated effect of Arab power was dramatically demonstrated. On that day, 105 member states of the United Nations voted to invite Yasser Arafat to address the Assembly on the Palestine problem. The moral significance of the vote was minor. Over the years, the automatic majority of the totalitarian, the antidemocratic, and the captive blocs had long turned the United Nations into a forum, pathetic yet potentially dangerous, whose deliberations bore little or no relation any longer to its high purpose. Now it was not only condoning murder and barbarity and legitimizing the threat of politicide and genocide, it was destroying its own formal legitimacy as an organization of recognized states with recognized minimal criteria. Among the 105 states, France and Italy also raised supporting hands, and of the other Western states, only three (apart from Israel)–Bolivia, the Dominican Republic, and the United States – were bold enough to vote in opposition. The rest abstained.

Now, too, the French government hastened to seek a further advantage over its fellow Western Europeans in subservience to the power-wielding Arabs. Foreign Minister Jean Sauvagnargues, paying an official visit to the Middle East, made his way first to Beirut and there (October 21) became the first Western Foreign Minister to shake the hand of Yasser Arafat. He greeted him effusively as “Mr. President” and, at a press conference, publicly pronounced his considered judgment of Arafat as “a moderate leader” possessed of the stature of a statesman who was “following a constructive path.” He did not elaborate. These events took place eighteen months after the slaughter of Western diplomats in Khartoum and five months after the massacre of children at Ma’alot.

The stage was now set for the Arab states to legitimize formally their intention to replace Israel with a “democratic secular State.” On October 29, 1974, the heads of the Arab states met in conference in Rabat, Morocco, and passed resolutions:

a. Reaffirming “the right of the Palestinian people to return to its Homeland”;

b. Reaffirming “the right of the Palestinian people to set up an independent national authority, under the leadership of the Palestine Liberation Organization as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, in every part of Palestine liberated. The Arab States are obligated to support this authority, from the moment of its establishment, in all spheres and at all levels”;

c. Expressing “support for the Palestine Liberation Organization in exercising its national and international responsibility within the framework of Arab undertakings.”

The decisions at Rabat were unanimous. Hussein of Jordan, who was deprived by the Rabat resolutions of any backing for his own claim to western Palestine, had long resigned himself to the reality that the terrorist movement was the more effective instrument for eliminating Israel. He could only hope that his acquiescence might evoke from the PLO a similar forbearance about having Transjordan in his hands, which, after all, they (correctly) regarded as eastern Palestine, and where in fact most of the Palestinian Arabs lived. He had long since been readmitted into the Arab fold. Egypt and Syria had reestablished relations with him on the eve of the October war, and he had then released the remaining terrorists – 756 in number – from his jails.

The resolutions were passed unanimously. President Sadat of Egypt, widely advertised by Western apologists as a “moderate,” did not pretend to try to introduce even a semantic modification of their plain language, moreover, whoever wished to could find many pronouncements by him or by other Egyptian authorities on their identity of purpose with the “Palestinian.” What Sadat intended for the Jews of Israel he had made plain in his widely publicized oath a year before the Yom Kippur War. He had sworn in the Cairo mosque to restore the Jews to the condition described in the Koran: “to be persecuted, oppressed and wretched.” It was Egypt’s leading weekly journal, AI-Musswar, that had spelt out in political terms precisely what was intended when the “legitimate rights” had been restored.

“The English word peace,” wrote the editor of the journal on December 7, 1973, “can be translated into Arabic as both sulh and salaam, whereas in Arabic there, is a difference between the two.”

Israel, he explained, could indeed expect salaam in exchange for a surrender to present Arab territorial demands (that is, to withdraw to the Armistice lines of 1949).

But sulh is another thing altogether. Sulh means that the Jews of Palestine–and I repeat and emphasize the expression, Jews of Palestine–will return to their senses and dwell under one roof and under one flag with the Arabs of Palestine, in a secular state devoid of any bigotry or racialism, proportional to their respective numerical ratio in 1948. By this I mean that the original Palestinian Jews and their children and grandchildren shall remain on the Palestinian soil and will live there with the original Palestinian Arabs. The Jews who came from abroad will return to their countries of origin, where they lived as did their forefathers before 1949 – for these countries bear them no ill will.

This article was a faithful paraphrase of the text of the constitution of the PLO—the socalled Palestine Covenant.

A fortnight after the Rabat Conference, clothed now with the unambiguous authority of the whole Arab world, Yasser Arafat delivered his address to the United Nations Assembly. His appearance was timed to coincide with the presidency for that month of an Arab, President Boumedienne of Algeria, who duly accorded to Arafat at the podium the treatment previously accorded only to heads of state. Nobody objected, nobody commented. Arafat did not disappoint his sponsors. Mounting a Soviet-style attack on imperialism and colonialism of which Zionism was the handmaiden, and repeating a fine selection of the calumnies gathered together by Arab calumniators of Zionism and the Jewish People, he called for world support for the elimination of the State of Israel and its replacement by a democratic secular State of Palestine. He did, however, make a concession to Western susceptibilities. Not all the Jews who bad arrived after 1948 would be deported. The Jews living in Israel could stay there, provided they agreed to accept whatever fate awaited them in the “democratic, secular State.”

The favoring wind that blew up for Arab ambitions after the October war had by now reached gale force. The campaign continued to accustom the world to the Nazistic idea that it would not be bad for the world if the Jewish state disappeared. Meantime, however, circumstances had made it possible for the Arabs to eliminate two other obstacles disturbing the homogeneity of Arab Moslem domination throughout the area between the Persian Gulf and the Atlantic Ocean.

One of these was the Kurds in Iraq, a Moslem but non-Arabic nation; the other the Christians of Lebanon. The Kurds, who had no state of their own, had been fighting for a generation in their contiguous territory in northern Iraq, not indeed for independence, but for autonomy within the Iraqi Arab state. Except for the occasions when they made promises (which were never kept) to grant such autonomy, successive Iraqi governments had tried without success to crash the Kurds by force.

Fierce and bloody resistance to Iraqi power was supported by Iranian arms, with United States backing. Iran’s support was a function of her ongoing dispute with Iraq about the sovereignty over the waterway dividing them. With the growingly profitable common oil interest and, presumably, prodded by the Arab League, the Iraqis, meeting the Iranians at an OPEC meeting in Morocco in Match 1975, made concessions in return for an Iranian abandonment of the Kurds. The Kurds were accorded one gesture. Those who wished to escape the mercies of the Arabs would, within a brief time limit, be allowed to cross the border into Iran and would be given sanctuary as refugees.

Inside the Kurdish region, the Iraqi government speedily applied plans for a final solution of the “problem.” It would be done by degrees.

Nearly 80 percent of the agricultural produce of the region was “bought” by the Iraqi government at a very low price, thus reducing the means of livelihood for the population. Moreover, nearly all doctors and medical personnel were transferred from the Kurdish region.

A plan to settle large numbers of Egyptians in the Kurdish region, and the building of three new towns for the purpose, was publicly described in an advertisement in At-Ahram of Cairo. Should nothing happen to disturb the process, the Kurdish entity was well launched for extinction.

The assault in Lebanon began a month later. It was not a walkover. Here was the only Arab state in which the Moslems had to share power and even to accept a minor share in it. Indeed, the original raison d’etre and the whole modern history of Lebanon was primarily of a Christian enclave, of a haven for Christians in an unfriendly Moslem environment. In recent years in particular, with the increasing discomforts and unease suffered by Christians in some of the Arab states, Christian immigrants from those countries were being absorbed by Lebanon. By the agreed Lebanese Constitution of 1943, the President and the Commander in Chief of the Army were always Christians, while a Moslem was Prime Minister. A Moslem was also Speaker in the Parliament, but the Christians held a majority of its seats.

The intolerance, of Moslems to a status less than domination had twice in the recent past led to violent efforts to put an end to this Christian predominance. On the last occasion, in 1958, order had been restored only after the United States had intervened by sending in Marines.

The Christians, well organized, forewarned by the new spirit of exhilaration and militancy that gripped the Arab Moslem world after the Yom Kippur War and by the ominous direction and thrust of American diplomacy, prepared for trouble. But they were faced by a coalition of forces. Their own Moslem neighbors, armed with weapons from Syria, were reinforced by the Arab terrorist organizations now filling without inhibition the role of executors of the pan-Arab will.

Incredibly, the fighting went on for months, mainly in Beirut, the capital. Large sections of the once flourishing westernized city, banking and business metropolis of all the Arab states, were reduced to rubble, and day after day tens, and later hundreds, of people, mostly civilians, were killed. After a year of civil war, at least twenty thousand people had perished.

By then the political objective of the Moslem onslaught had been accomplished. Whatever the precise organization of the country turned out to be, Christian predominance had been brought to an end. The army had been broken up into its religious components and had I ,fact disintegrated as a viable force. The Christian President, whose resignation was demanded by the Moslem insurgents, was finally replaced by a cowed majority vote in a besieged Parliament; his successor was a Christian nominated by the Syrians.

The continued shelling and shooting reflected the sense of desperation of the Christians, who could not reconcile themselves to defeat. But more incisive was the fact that the Moslems, having achieved the essential political victory, quarreled over the spoils.

The Syrian government now found the moment ripe to achieve her own special objective to take the affairs of Lebanon under her control as a first step toward the creation of the long-dreamed-of Greater Syria. Yet the Lebanese Moslems had believed that the struggle and indeed the sacrifice had been for their benefit. The terrorist organizations, who, had played their part in reducing the Christians, regarded it as their natural right to play a dominant role in deciding the fate of Lebanon.

The grotesquerie of the events was now made complete. The Christian nations, who with more or less embarrassment had throughout the months kept silent and turned their faces from the slaughter that Syria, had generated and sustained, now welcomed her, and the troops she sent into Lebanon, as a ” Peacemaker.”

The precise roles and relationship of the Syrians, the Lebanese Moslems, and the Palestinian terrorist organizations would soon crystallize. The reduction of the penultimate vestige of non-Moslem sovereignty in the Arab world would now also bring about, along the southern Lebanese border. A fourth front manned by a variety of Arabs, all in “Palestinian” uniforms, for the final reduction of Israel – the last obstacle to the “unity of the Arab world.”

Pending the realization of their ideal of Israel’s physical elimination, the Arab states pursued with undiminished vigor the preparatory gnawing and nibbling at Israel’s Status as a member of the community of nations. Their tactics were strikingly similar to those of the Nazis: to disseminate an image of Israel – and of the Jewish people – as black, as negative and as hateful as could be conjured up by their own fertile imaginations and by the anti-Semitic outpourings of the ages so that when the time and the opportunity came to destroy Israel physically, the normal reactions, even of civilized people, would be blunted and minimal. At the same time, they accustomed the world to spectacles symbolizing the supplanting of Israel by the “Palestinians.”

They had as yet no hope of achieving Israel’s expulsion from the United Nations or even of the application of sanctions against her – both decisions subject to veto in the Security Council – but in the meantime they secured majority decisions denouncing Israel and indeed the concept of Jewish nationalism in a number of international bodies unconcerned with politics. They succeeded even in having Israel expelled from the regional section of UNESCO to which she belonged (and to whose work she contributed far beyond her logical share). The protests and resignations of intellectuals, artists, and scientists throughout the world were to no avail. Thus, also, Israel was excluded from Asian sporting bodies. And, thus, the United Nations Assembly passed a resolution equating Zionism with racism.

This last obscenity was indeed too much for the Western nations to stomach. Not only did they not hide their disgust, but thirty-four of them voted against the resolution.

Yet this isolated act of protest revealed all the more sharply the supine resignation of the Western nations toward nearly all the other Arab-Soviet orchestrated efforts to turn Israel into a pariah state, and which had already made a grotesque caricature of the United Nations organization. Mr. Abba Eban, the former foreign Minister of Israel, once remarked–before the Yom Kippur War—that if the Arabs were to introduce a resolution at the UN declaring the earth to be flat, they would get forty supporting votes. in the now enlarged United Nations, and in today’s circumstances, they would probably muster 110. And the Western nations would abstain. This is the essence of their record on the Arabs’ hate campaign against Israel. Afraid to offend the Arabs, yet unable to support them in conscience, or where no plausible excuse was available, they would seek discreet refuge in abstention, however absurd, irrelevant, or outrageous the Arab resolution might be.

On the other hand, the Western nations equally supinely showed no resistance to the seating of the PLO on various international bodies engaged in practical day-to-day activities, treating that organization as though it were a national authority relating to the territory of Palestine.

It is weird and depressing to see the rapists of Czechoslovakia and those who savaged Yemen, the destroyers of the Kurds and those who murdered the South Sudanese, the vicious racists from Uganda and the begetters of the bloodbath in Lebanon, conferring in the corridors of the United Nations in amity and parliamentary decorum with the spokesmen for Western civilization, wrestling over a formula for their diverse, selfish (or imagined) interest that would somehow break the resistance and the spirit of Israel, while all aver that their only objects are peace and justice. As long as this collaboration continues, there can be neither peace nor justice in Palestine, but at best a ceasefire with recurring Arab efforts at attrition.

We would like to thank ShmuelKatz.com for providing us with the material for this article. This article is republished with the permission of David Isaac, e-Editor of ShmuelKatz.com. For republishing rights please contact David Isaac directly at David_Isaac@ShmuelKatz.com.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

About the author,

Shmuel “Mooki” Katz, born Samuel Katz (9 December 1914 – 9 May 2008) was an Israeli writer, member of the first Knesset, publisher, historian and journalist. He is also known for his research on Jewish leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky.

Katz was born in 1914 in South Africa, and in 1930 he joined the Betar movement. In 1936 he immigrated to Mandate Palestine and joined the Irgun. In 1939 he was sent to London by Ze’ev Jabotinsky to speak on issues concerning Palestine. While there he founded the revisionist publication “The Jewish Standard” and was its editor, 1939–1941, and in 1945. In 1946 Katz returned to Mandate Palestine and joined the HQ of the Irgun where he was active in the aspect of foreign relations. He was one of the seven members of the high command of the Irgun, as well as a spokesman of the organization.

In 1948 Katz assisted in the bringing of the ship, Altalena to the shores of Israel. Shmuel Katz was one of the founders of the Herut political party and served as one of its members in the First Knesset. In 1951 he left politics and managed the Karni book publishing firm. He was co-founder of The Land of Israel Movement in 1967, and in 1971 he helped to create Americans for a Safe Israel.

In 1977 Katz became “Adviser to the Prime Minister of Information Abroad” to Menachem Begin. He accompanied Begin on two trips to Washington and was asked to explain some points to President Jimmy Carter. He quit this task on January 5, 1978 because of differences with the Cabinet over peace proposals with Egypt. He refused the high prestige post of UN ambassador. Katz was then active with the Tehiya party for some years and later with Herut – The National Movement after it split away from the ruling Likud. He also has written for the Daily Express and The Jerusalem Post. (source: wikipedia and shmuelkatz.com)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment