The Jewish Presence in Palestine

Posted by Crethi Plethi on Sun, November 14, 2010, in Arab-Israeli Conflict, Fact and Fantasy, Islamic Countries, Israel, Israel Defense Forces, Israeli–Palestinian Conflict, The Middle East . Sun, Nov 14, 2010

shmuelkatz.com

By Shmuel Katz

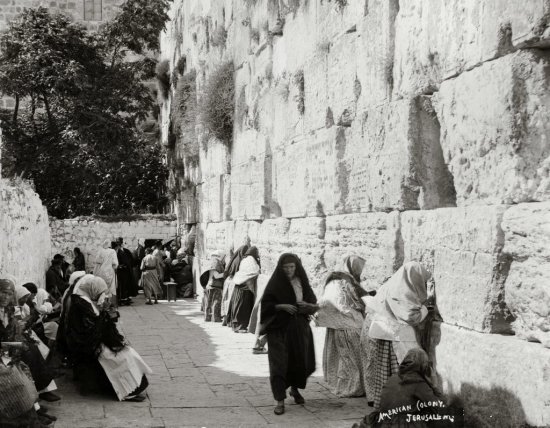

Jews praying at Western Wall, Jerusalem, early 1900s (Source: The American Colony and Eric Matson Collection: Jerusalem)

Battleground: Fact and Fantasy in Palestine

The Jewish Presence in Palestine

This article is the fourth chapter from the book “Battleground: Fact and Fantasy in Palestine” written by Shmuel Katz. Yesterday, we published the third chapter: The Origin of the Dispute. In the next few days, we will publish the rest of the chapters from this book as part of a series of facts, fantasy and myths concerning Israel, Palestinians and the Middle East. For all the chapters of the book, click Here.

About the book: “A fully documented, dramatic history of the events which shaped the Middle East. Every key problem in the Arab-Israel conflict, every decision is carefully analyzed, from the questionable policies of Britain in 1948 to how the Palestinian refugee problem began. The territory won in the war of 1967, and the terrorist war of attrition is discussed.” (From the intro at ShmuelKatz website). To view the entire book online, go to Shmuelkatz.com. To buy the book, go to Afsi.org.

Promoted by two such powerful forces as Soviet assertions and Arab propaganda, the claim of Arab historical rights has become a central element in the international debate. By sheer weight of noise, it has impressed many otherwise knowledgeable and well meaning people. The facts of history are thus a vital element to understanding the conflict over Palestine and for placing it in its proper perspective. They are all readily ascertainable.

In our day, we are witnessing an astonishing phenomenon demonstrating and dramatizing the depth of attachment to the land of Israel in the heart by Jews long alienated from it both physically and spiritually: the explosion of Zionism among the Jewish youth of the Soviet Union.

For fully fifty years the Soviet state, clothed with totalitarian authority, by its very nature brooking no other ideology, has labored to indoctrinate its people with the Communist faith. Hostile to all religions, the Soviet regime has made a special, purposeful effort to eradicate Judaism. It has achieved the closing down of most of the synagogues in the country; there are no Jewish religious schools or classes in the Soviet Union. After thirty, forty, fifty years, as the third generation of Soviet-educated, Soviet indoctrinated young Jews grew up, only faint remnants of Jewish religious observance, survived.

The idea of the return of the Jewish people to Palestine was outlawed by the Soviet regime. For nearly thirty years Zionism was denounced as an instrument of British imperialism and of international capitalism, as an enemy of the Soviet state and of Communism.

It was a crime in the Soviet code. At different times, tens of thousands of Jews were jailed or toiled and suffered – and often died – in Siberian exile for no other reason than that they were declared or suspected Zionists. Hostility to Zionism has found ever more violent expression in concentrated enmity to the State of Israel.

By its very nature and content, Soviet education not only insured that young Jews should not be taught the faith of their fathers, but also subjected them throughout their formative years to a curriculum of hatred and contempt for the ideas, values, and achievements of Zionism.

While the first generation of Jews in the era of the Bolshevik Revolution may have been able to inspire some spiritual resistance in the hearts of its sons, that little had all but evaporated when, after the creation of the Jewish state, the sons were faced with the task of rearing the third generation. No wonder, then, that twenty-five years ago many of us in the West assumed that the Soviet Union had probably succeeded in forcing assimilation on the Jews of the USSR, that where indoctrination and suppression had not entirely succeeded in the first generation, sheer ignorance in the second and third would complete the process.

In fact, under the surface, a completely different spiritual transformation was taking place. It came to fulfillment precisely in the third generation – whose parents were born and reared in the embrace of the Soviet state. It incubated and grew slowly. Only from time to time were there public signs of nonconformism. It became explosive after the Six Day War.

In the years since 1967, the Jewish community in the Soviet Union has become a boiling cauldron. The third generation, the sons of the “lost” generation, are visibly restless with longing for this land they have never seen and of which they know very little. They have made manifest a fierce sense of alienation from the society that reared them and a passion of oneness with the Jewish people against whom their whole education and the culture of their upbringing has nurtured them. A movement has spread throughout the Soviet Union in spite of the totalitarian repression of the regime. This movement is one of young people, challenging the very core of Soviet indoctrination.

It started in the secret study of Hebrew, which was frowned upon, in copying and spreading literature about Israel, which was by definition forbidden, in word-of-mouth dissemination of news gleaned from foreign radio broadcasts. Many of the young Jews emerged from their anonymity. At the very moment that the Soviet Union exchanged its, long-standing policy of arming and backing the forces arrayed against Israel for a policy of direct physical intervention on their behalf, these young Soviet Jews boldly addressed the authorities, proclaiming their renunciation of identification with the Soviet state. They demanded the fulfillment of their right – formally entrenched in the Soviet Constitution but denied by Soviet policy – to leave the Soviet Union and to join the Jewish people in their homeland. They also drew many of their parents out of their timidity; the Soviet Home Office was flooded with numerous applications by whole families in the tens of thousands. Defying the states capacity for retribution and its potential for punishment, they declared their desire to give up their Soviet citizenship, give up all they have in the Soviet Union, and go, “on foot if necessary,” to join their people in the State of Israel.

For a variety of alleged offenses committed in the process, many of them have been sent to jail or, in a few cases, to mental homes. In response, far from deterring others, has spurred them on to more and more defiant action. An unsuccessful attempt to hijack a Soviet plane and thus fly to freedom; unprecedented demonstrations of protest by groups of Jews inside Soviet government offices; the passion that alone could make possible such an explosion of defiance are all powerful indications that a form of Zionist rebellion is in progress inside the Soviet Union.

The emergence and the progressive intensification of Jewish national identification in the Soviet Union has seemed miraculous even to many historically minded people. It is, in fact, merely an expression sharpened, deepened, and concentrated by the circumstances of the central fact of 3,500 years of Jewish history: the passion of the Jewish people for the land of Israel. The circumstances in which the Jewish people, its independence crushed nineteen centuries ago and large numbers of its sons driven into exile, maintained and preserved its connection with the land are among the most remarkable facts in the story of mankind. For eighteen centuries, the Zionist passion – the longing for Zion, the dream of the restoration, and the ordering of Jewish life and thought to prepare for the return – pulsed in the Jewish people. That passion finally gave birth to the practical and political organizations which, amid the storms of the twentieth century, launched the mass movement for the return to Zion and for restored Jewish national independence.

The Jews were never a people without a homeland. Having been robbed of their land, Jews never ceased to give expression to their anguish at their deprivation and to pray for and demand its return. Throughout the nearly two millennia of dispersion, Palestine remained the focus of the national culture. Every single day in all those seventy generations, devout Jews gave voice to their attachment to Zion.

The consciousness of the Jew that Palestine was his country was not a theoretical exercise or an article of theology or a sophisticated political outlook. It was in a sense all of these – and it was a pervasive and inextricable element in the very warp and woof of his daily life. Jewish prayers, Jewish literature, are saturated with the love and the longing for and the sense of belonging to Palestine. Except for religion and the love between the sexes, there is no theme so pervasive in the literature of any other nation, no theme has yielded so much thought and feeling and expression, as the relationship of the Jew to Palestine in Jewish literature and philosophy. And in his home on family occasions, in his daily customs on weekdays and Shabbat, when he said grace over meals, when he got married, when he built his house, when he said words of comfort to Mourners, the context was always his exile, his hope and belief in the return to Zion, and the reconstruction of his homeland. So intense was this sense of affinity that, if in the vicissitudes of exile he could not envisage that restoration during his lifetime, it was a matter of faith that with the coming of the Messiah and the Resurrection he would be brought back to the land after his death.

Over the centuries, through the pressures of persecution – of social and economic discrimination, of periodic death and destruction – the area of exile widened. Hounded and oppressed, the Jews moved from country to country. They carried Eretz Israel with them wherever they went. Jewish festivals remained tuned to the circumstances and conditions of the Jewish homeland. Whether they remained in warm Italy or Spain, whether they found homes in cold Eastern Europe, whether they found their way to North America or came to live in the southern hemisphere where the seasons are reversed, the Jews celebrated the Palestinian spring and its autumn and winter. They prayed for dew in May and for rain in October. On Passover they ceremonially celebrated the liberation from Egyptian bondage, the original national establishment in the Promised Land – and they conjured up the vision of a new liberation.

Never in the periods of greatest persecution did the Jews as a people renounce that faith. Never in the periods of greatest peril to their very existence physically, and the seeming impossibility of their ever regaining the land of Israel, did they seek a substitute for the homeland. Time after time throughout the centuries, there arose bold spirits who believed, or claimed, they had a plan, or a divine vision, for the restoration, of the Jewish people to Palestine. Time after time a wave of hope surged through the ghettos of Europe at the news of some new would-be Messiah. The Jews’ hopes were dashed and the dream faded, but never for a day did they relinquish their bond with their country.

There were Jews who fell by the wayside. Given a choice under torture, or during periods of civic equality and material prosperity, they foresook their religion or turned their backs on their historic country. But to the people, the land – as it was called for all those centuries: simply Ha’aretz, the Land – remained the one and only homeland, unchanging and irreplaceable.

If ever a right has been maintained by unrelenting insistence on the claim, it was the Jewish right to Palestine.

Widely unknown, its significance certainly long ungrasped, is the no less awesome fact that throughout the eighteen centuries between the fall of the Second Jewish Commonwealth and the beginnings of the Third, in our time, the tenacity of Jewish attachment to the land of Israel found continuous expression in the country itself. It was long believed – and still is – even in some presumably knowledgeable quarters, that throughout those centuries there were no Jews in Palestine. The popular conception has been that all the Jews who survived the Destruction of 70 C.E. went into exile and that their descendants began coming back only 1,800 years later. This is not a fact. One of the most astonishing elements in the history of the Jewish people – and of Palestine – is the continuity, in the face of the circumstances of Jewish life in the country.

It is a continuity that waxed and waned, that moved in kaleidoscopic shifts, in response to the pressures of the foreign imperial rulers who in bewildering succession imposed themselves on the country. It is a pattern of stubborn refusal, in the face of oppression, banishment, and slaughter, to let go of an often tenuous hold in the country, a determined digging in sustained by a faith in the ultimate fall restoration, of which every Jew living in the homeland saw himself as caretaker – and precursor.

This people that was “not here” – the Jewish community in Palestine, its history continuous and purposeful – in fact played a unique role in Jewish history. Too often lacking detail and depth, the story of the Jewish presence in Palestine, threaded together from a colorful variety of sources and references, pagan and Christian, Jewish and Moslem, spread over the whole period between the second and the nineteenth centuries, is a fascinating and compelling counterpoint to the dominating theme of the longing-in-exile.

Only when they had crushed the revolt led by Simon Bar Kochba in 135 C.E. – over sixty years after the destruction of the Second Temple – did the Romans make a determined effort to stamp out Jewish identity in the Jewish homeland. They initiated the long process of laying the country waste. It was then that Jerusalem, “plowed over” at the order of, Hadrian, was renamed Aelia Capitolina, and the country, denied of the name Judea, was renamed Syria Palestina. In the revolt itself–the fiercest and longest revolt faced by the Roman Empire – 580,000 Jewish soldiers perished in battle, and an untold number of civilians died of starvation and pestilence; 985 villages were destroyed.

Yet even after this further disaster, Jewish life remained active and productive. Banished from Jerusalem, it now centered on Galilee. Refugees returned; Jews who had been sold into slavery were redeemed. In the centuries after Bar Kochba and Hadrian, some of the most significant creations of the Jewish spirit were produced in Palestine. It was then that the Mishnah was completed and the Jerusalem Talmud was compiled, and the bulk of the community farmed the land.

The Roman Empire adopted Christianity in the fourth century; henceforth its policy in Palestine was governed by a new purpose: to prevent the birth of any glimmer of renewed hope of Jewish independence.

It was, after all, basic to Christian theology that loss of national independence was an act of God designed to punish the Jewish people for their rejection of Christ The work of the Almighty had to be helped along. Some emperors were more lenient than others, but the minimal criteria of oppression and restriction were nearly always maintained.

Nevertheless, even the meager surviving sources name forty-three Jewish communities in Palestine in the sixth century: twelve towns on the coast, in the Negev, and east of the Jordan, and thirty-one villages in Galilee and in the Jordan valley.

The Jews’ thoughts at every opportunity turned to the hope of national restoration. In the year 351, they launched yet another revolt, provoking heavy retribution. When, in 438, the Empress Eudocia removed the ban on Jews’ praying at the Temple site, the heads of the Community in Galilee issued a call “to the great and mighty people of the Jews” which began: “Know then that the end of the exile of our people has come”!

In the belief of restoration to come, the Jaws made an alliance with the Persians who invaded Palestine in 614, fought at their side, overwhelmed the Byzantine garrison in Jerusalem, and for three years governed the City. But the Persians made their peace with the Emperor Heraclius. Christian rule was reestablished, and those Jews who survived the consequent slaughter were once more banished from the city. A new chapter of vengeful Byzantine persecution was enacted, but as it happened, it was short-lived. A new force was on the march. In 632, the Moslem Arab invaders came and conquered. By the year 640, Palestine had become a part of the emerging Moslem empire.

The 450-year Moslem rule in Palestine was first under the Omayyads (predominantly Arab), who governed tolerantly from Damascus; then under the Abbasid dynasty (predominantly Turkish), in growing anarchy, from Baghdad; and finally, in alternating tolerance and persecution, under the Fatimids from Cairo. The Moslem Arabs took from the Jews the lands to which they had clung for twenty generations after the fall of the Jewish state. The Crusaders, who came after them and ruled Palestine or parts of it for the better part of two centuries, massacred, the Jews in the cities. Yet, under the Moslems openly, under the Crusaders more circumspectly, the Jewish community of Palestine, in circumstances it is impossible to understand or to analyze, held on by the skin of its teeth, somehow survived, and worked, and fought. Fought. Along with the Arabs and the Turks, the Jews were among the most vigorous defenders of Jerusalem against the Crusaders. When the city fell, the Crusaders gathered the Jews in a synagogue and burned them. The Jews almost single-handedly defended Haifa against the Crusaders, holding out in the besieged town for a whole month (June-July 1099). At this time, a full thousand years after the fall of the Jewish state, there were Jewish communities all over the country. Fifty of them are known to us; they include Jerusalem, Tiberias, Ramleh, Ashkelon, Caesarea, and Gaza.

During more than six centuries of Moslem and Crusader rule, periods of tolerance or preoccupied indifference flickered fitfully between periods of concentrated persecution. Jews driven from the villages, fled to the towns. Surviving massacre in the inland towns, they made their way to the coast. When the coastal towns were destroyed, they succeeded somehow in returning inland. Throughout those centuries, war was almost continuous, whether between Cross and Crescent or among the Moslems themselves. The Jewish community, now heavily reduced, maintained itself in stiff-necked endurance.

Moslem and Christian records report that they pursued a variety of occupations. The Arab geographer Abu Abdallah Mohammed-known as Mukadassi – writing in the tenth century, describes the Jews as the assayers Of coins, the dyers, the tanners, and the bankers in the community. In his time, a period of Fatimid tolerance, many Jewish officials were serving the regime. While they were not allowed to hold land in the Crusader period, the Jews controlled much of the commerce of the coastal towns during times of quiescence. Most of them were artisans: glass blowers in Sidon, furriers and dyers in Jerusalem.

In the midst of all their vicissitudes and in the face of all change, Hebrew scholarship and literary creation went on flourishing. It was in this period that the Hebrew grammarians at Tiberias evolved their Hebrew vowel-pointing system, giving form to the modern study of the language; and a large volume of piyutim and midrashim had their origin in Palestine in those days.

After the Crusaders, there came a period of wild disturbance as first the Kharezmians – an Asian tribe appearing fleetingly on the stage of history – and then the Mongol hordes, invaded Palestine. They sowed new rain and destruction throughout the country. Its cities were laid waste, its lands were burned, its trees were uprooted, the younger part of its population was destroyed.

Yet the dust of the Mongol hordes, defeated by the Mamluks, had hardly settled when the Jerusalem community, which had been all but exterminated, was reestablished. This was the work of the famous scholar Moses ben Nachman (Nachmanides, the, “RaMbaN”) . From the day in 1267 when RaMbaN settled in the city, there was a coherent Jewish community in the Old City of Jerusalem until it was driven out, temporarily as it proved, by the British-led Arab Legion from Transjordan nearly seven hundred years later.

For two and a half centuries (1260-1516), Palestine was part of the Empire of the Mamluks, Moslems of Turkish-Tartar origin who ruled first from Turkey, then from Egypt. War and uprisings, bloodshed and destruction, flowed in almost incessant waves across their domain. Though Palestine was not always involved in the strife, it was frequently enough implicated to hasten the process of physical destruction Jews (and Christians) suffered persecution and humiliation. Yet toward the end of the rule of the Mamluks, at the close of the fifteenth century, Christian and Jewish visitors and pilgrims noted the presence of substantial Jewish communities. Even the meager records that survived report nearly thirty Jewish urban and rural communities at the opening of the sixteenth century.

By now nearly fifteen hundred years had passed since the destruction of the Jewish state. Jewish life in Palestine had survived Byzantine ruthlessness, had endured the discriminations, persecutions, and massacres of the variegated Moslem sects – Arab Omayyads, Abbasids, and Fatimids, the Turkish Seljuks, and the Mamluks. Jewish life had by some historic sleight of hand out lived the Crusaders, its mortal enemy. it had survived Mongol barbarism.

More than an expression of self-preservation, Jewish life had a purpose and a mission. It was the trustee and the advance guard of restoration. At the close of the fifteenth century, the pilgrim Arnold Van Harff reported that he had found many Jews in Jerusalem and that they spoke Hebrew. They told another traveler, Felix Fabri that they hoped soon to resettle the Holy Land.

During the same period, Martin Kabatnik (who did not like Jews), visiting Jerusalem during his pilgrimage, exclaimed:

The heathens oppress them at their pleasure. They know that the Jews think and say that this is the Holy Land that was promised to them. Those of them who live here are regarded as holy by the other Jews, for in spite of all the tribulations and the agonies they suffer at the hands of the heathen, they refuse to leave the place.

At the height of their splendor, in the first generations after their conquest of Palestine in 1516, the Ottoman Turks were tolerant and showed, a friendly face to the Jews. During the sixteenth century, there developed a new effervescence in the life of the Jews in the country. Thirty communities, urban and rural, are recorded at the opening of the Ottoman era. They include Haifa, Sh’chem, Hebron, Ramleh, Jaffa, Gaza, Jerusalem, and many in the north. Their center was Safed; its community grew quickly. It became the largest in Palestine and assumed the recognized spiritual leadership of the whole Jewish world. The luster of the cultural “golden age” that now developed shone over the whole country and has, inspired Jewish spiritual life to the present day. It was there and then that a phenomenal group of mystic philosophers evolved the mysteries of the Cabala. It was at that time and in the inspiration of the place that Joseph Caro compiled the Shulhan Aruch, the formidable codification of Jewish observance, which largely guides orthodox custom to this day. Poets and writers flourished. Safed achieved a fusion of scholarship and piety with trade, commerce, and agriculture. In the town, the Jews developed a number of branches of trade, especially in grain, spices, and cloth. They specialized once again in the dyeing trade. Lying halfway between Damascus and Sidon on the Mediterranean coast, Safed gained special importance in the commercial relations in the area. The 8,000 or 10,000 Jews in Safed in 1555 grew to 20,000 or 30,000 by the end of the century.

In the neighboring Galilean countryside, a number of Jewish villages – from Turkish sources we know of ten of them – continued to occupy themselves with the production of wheat and barley and cotton, vegetables and olives, vines and fruit, pulse and sesame.

The recurrent references in the sketchy records that have survived suggest that in some of those Galilean villages – such as Kfar Alma, Ein Zeitim, Biria, Pekiin Kfar Hanania, Kfar Kana, Kfar Yassif – the Jews, against all logic and in defiance of the pressures and exactions and, confiscations of generation after generation of foreign conquerors had succeeded in clinging to the land for fifteen centuries. Now for several decades of benevolent Ottoman rule, the Jewish communities flourished in village and town.

The history of the second half of the sixteenth century illustrates the dynamism of the Palestinian Jews their prosperity, their progressiveness, and their subjugation. In 1577, a Hebrew printing press was established in Safed. The first press in Palestine, it was also the first in Asia. In 1576, and again in 1577, the Sultan Murad III, the first anti-Jewish, Ottoman ruler, ordered the deportation of 1,000 wealthy Jews from Safed, though they had not broken any laws or transgressed in any way. They were needed by Murad to strengthen the economy of another of the Sultan’s provinces – Cyprus. It is not known whether they were in fact, deported or reprieved.

The honeymoon period between the Ottoman Empire and the Jews lasted only as long as the empire flourished. With the beginning and development of its long decline in the seventeenth century, oppression and anarchy made growing inroads into the country, and Jewish life began to follow a confused pattern of persecutions, prohibitions, and ephemeral prosperity. Prosperity grew rarer, persecutions and oppressions became the norm. The Ottomans, to whom Palestine was merely a source of revenue, began to exploit the Jews fierce attachment to Palestine. They were consequently made to pay a heavy price for living there. They were taxed beyond measure and were subjected to a system of arbitrary fines. Early in the seventeenth century, two Christian travelers, Johann van Egmont and John Hayman, could say of the Jews in Safed: “Life here is the poorest and most miserable that one can imagine.”

The Turks so oppressed them, they wrote, that “they pay for the very air they breathe.” Again and again during the three centuries of Turkish decline, the Jews so lived and bore themselves that even hostile Christian travelers were moved to express their astonishment at their pertinacity – despite suffering, humiliation, and violence – in clinging to their homeland.

The Jews of Jerusalem, wrote the Jesuit Father Michael Naud in 1674, were agreed about one thing:

“paying heavily to the Turk for their right to stay here. . . . They prefer being prisoners in Jerusalem to enjoying the freedom they could acquire elsewhere…The love of the Jews for the Holy Land, which they lost through their betrayal [of Christ], is unbelievable. Many of them come from Europe to find a little comfort, though the yoke is heavy.”

And not in Jerusalem alone. Even as anarchy spread over the land, marauding raids by Bedouins from the desert increased, and the roads became further infested with bandits, and while the Sultan’s men, when they appeared at all, came only to collect both the heavy taxes directed against all and the special taxes exacted from the Jews, Jewish communities still held on all over the country. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, travelers reported them in Hebron (where, in addition to the regular exactions, threats of deportation, arrests, violence, and bloodshed, the Jews suffered the gruesome tribulations of a blood libel in 1775); Gaza, Ramleh, Sh’chem, Safed (where the community had lost its preeminence and its prosperity); Acre, Sidon, Tyre, Haifa, Irsuf, Caesarea, and El Arish; and Jews continued to live and till the soil in Galilean villages.

But as the country itself declined and the bare essentials of life became inaccessible, the Jewish community also contracted. By the end of the eighteenth century, historians’ estimates put their number at between 10,000 and 15,000. Their national role, however, was never blurred. When the Jews in Palestine had no economic basis, the Jews abroad regarded it as their minimum national duty to insure their physical maintenance, and a steady stream of emissaries brought back funds from the Diaspora. In the long run, this had a degrading effect on those Jews who came to depend on these contributions for all their needs. But the significance of the motive and spirit of the aid is not lessened: the Jews in Palestine were regarded as the guardians of the Jewish heritage. Nor can one ignore the endurance and pertinacity of the recipients, in the face of oppression and humiliation and the threat of physical violence, in their role of “guardians of the walls.”

However determined the Jews in Palestine might have been, however deep their attachment to the land, and however strong their sense of mission in living in it, the historic circumstances should surely have ground them out of physical existence long before the onset of modern times.

Merely to recall the succession of conquerors who passed through the country and who oppressed or slaughtered Jews, deliberately or only incidentally to their struggle for power or survival, raises the question of how any Jews survived at all, let alone in coherent communities. Pagan Romans, Byzantine Christians, the various Moslem imperial dynasties (especially during the Seljuk Turkish interlude, before the Crusaders), the Crusaders themselves, the Kharezmians and the Mongols, the Ottoman Turks – all these passed over the body of the Jewish community.

How then did a Jewish community survive at all? How did it survive as an arm of the Jewish people, consciously vigilant for the day of national restoration?

The answer to these questions reflects another aspect of the phenomenal affinity of the Jewish people to the Land of Israel. In spite of bans and prohibitions, in spite of the most improbable and unpromising circumstances, there was never a period throughout the centuries of exile without Jewish immigration to Palestine. Aliyah (”going up”) was a deliberate expression and demonstration of the national affinity to the land. A constant inflow gave life and often vigor to the Palestinian community. By present-day standards, the numbers were not great. By the standards of those ages, and in the circumstances of the times, the significance and weight of that stream of aliyah – almost always an individual undertaking – matches the achievements of the modem Zionist movement.

Modern Zionism did indeed start the count of the waves of immigration after 1882, but only the frame and the capacity for organization were new: The living movement to the land had never ceased. The surviving records are meager. There was much movement during the days of the Moslem conquest. Tenth century appeals for aliyah by the Karaite leaders in Jerusalem have survived. There were periods when immigration was forbidden absolutely; no Jew could “legally” or safely enter Palestine while the Crusaders ruled. Yet precisely in that period, Yehuda Halevi, the greatest Hebrew poet of the exile, issued a call to the Jews to emigrate, and many generations drew active inspiration from his teaching. (He himself died soon after his arrival in Jerusalem in 1141, crushed, according to legend, by a Crusader’s horse.) A group of immigrants who came from Provence in France in the middle of the twelfth century must have been scholars of great repute, for they are believed to have been responsible for changing the Eretz Israel tradition of observing the New Year on only one day; ever since their time, the observance has lasted two days. There are slight allusive records of other groups who came after them. Among the immigrants who began arriving when the Crusaders’ grip on Palestine had been broken by Saladin was an organized group of three hundred rabbis who came from France and England in 1210 to strengthen especially the Jewish communities of Jerusalem, Acre, and Ramleh. Their work proved vain. A generation later came the destruction by the Mongol invaders. Yet no sooner had they passed than a new immigrant, Moses Nachmanides, came to Jerusalem, finding only two Jews, a dyer and his son; but he and the disciples who answered his call reestablished the community. Though Yehuda Halevi and Nachmanides were the most famous medieval preachers of aliyah, they were not the only ones. From the twelfth century onward, the surviving writings of a long series of Jewish travelers described their experiences in Palestine. Some of them remained to settle; all propagated the national duty and means of individual redemption of the “going up” to live in the homeland.

The concentrated scientific horror of the Holocaust in twentieth-century Europe has perhaps weakened the memory of the experience of the people to whom, year after year, generation after generation, Europe was purgatory. Those, after all, were the Middle Ages; those were the centuries when the Jews of Europe were subjected to the whole range of persecution, from mass degradation to death after torture. For a Jew who could not and would not hide his identity to make his way from his own familiar city or village to another, from the country whose language he knew through countries foreign to him, meant to expose himself almost certainly to suspicion, insult, and humiliation, probably to robbery and violence, possibly to murder. All travel was hazardous. For a Jew in the thirteenth, fourteenth, or fifteenth century (and even later) to set out on the odyssey from Western Europe to Palestine was a heroic undertaking, which often ended in disaster. To the vast mass of Jews sunk in misery, whose joy it was to turn their faces eastward three times daffy and pray for the return to Zion, that return in their lifetime was a dream of heaven.

There were periods, moreover, when the Popes ordered their adherents to prevent Jewish travel to Palestine. For most of the fifteenth century, the Italian maritime states denied Jews the use of ships for getting to Palestine, thus forcing them to abandon their project or to make the whole journey by a roundabout land route, adding to the initial complications of their travel the dangers of movement through Germany, Poland, and southern Russia, or through the inhospitable Balkans and a Black Sea crossing before reaching the comparative safety of Turkey. In 1433, shortly after the ban was imposed, there came a vigorous call by Yitzhak Tsarefati, urging the Jews to come by way of then tolerant Turkey. Immigration of the bolder spirits continued. Often the journey took years, while the immigrant worked at the intermediate stopping places to raise the expenses for the next leg of his journey or, as sometimes happened, while he invited the local rich Jews to finance his journey and to share vicariously in the mitzvah of his aliyah. Siebald Rieter and Johann Tucker, Christian pilgrims visiting Jerusalem in 1479, wrote down the route and stopping places of a Jew newly arrived as an immigrant from Germany. He had set out from Nuremberg and traveled to Posen (about 300 miles).

Then Posen [Poznan] to Lublin 250 miles;

Lublin to Lemberg [Lvov] 120 miles;

Lemberg to Khotin 150 miles;

Khotin to Akerman 150 miles;

Akerman, to Samsun 6 days;

Samsun to Tokat 6-7 days;

Tokat to Aleppo 15 days;

Aleppo to Damascus 7 days;

Damascus to Jerusalem 6 days.

The Ottoman Sultans had encouraged Jewish immigration into their dominions. With their conquest of Palestine, its gates too were opened. Though conditions in Europe made it possible for only a very few Jews to “get up and go,” a stream of immigrants flowed to Palestine at once. Many who came were refugees from the Inquisition. They comprised a great variety of occupations; they were scholars and artisans and merchants. They filled all the existing Jewish centers. That flow of Jews from abroad injected a new pulse into Jewish life in Palestine in the sixteenth century. As the Ottoman regime deteriorated, the conditions of life in Palestine grew harsher, but waves of immigration continued. In the middle of the seventeenth century, there passed through the Jewish people an electric current of self-identification and intensified affinity with its homeland. For the first time in Eastern Europe, which had given shelter to their ancestors fleeing from persecution in the West, rebelling Cossacks in 1648 and 1649 subjected the Jews to massacre as fierce as any in Jewish history. Impoverished and helpless, the survivors fled to the nearest refuge – now once more in Western Europe. Again the bolder spirits among them made their way to Palestine. That same generation was electrified once more by the advent of Shabbetai Zevi, the self-appointed Messiah whose imposture and whose following among the Jews in both the East and the West was made possible only by the unchanged aspirations of the Jews for restoration. The dream of being somehow wafted to the land of Israel under the banner of the Messiah evaporated, but again there were determined men who somehow found the means and made their way to Palestine, by sea or by stages overland through Turkey and Syria.

The degeneration of the central Ottoman regime, the anarchy in the local administration, the degradations and exactions, plagues and pestilence, and the rain of the country, continued in the eighteenth and well into the nineteenth century. The masses of Jews in Europe were living in greater poverty than ever. Yet immigrants, now also in groups, continued to come. Surviving letters tell about the adventures of groups who came from Italy, Morocco, and Turkey. Other letters report on the steady stream of Hasidim, disciples of the Baal Shem-Tov, from Galicia and Lithuania, proceeding during the whole of the second half of the eighteenth century.

It is clear that by now the state of the country was exacting a higher toll in lives than could be replaced by immigrants. But the immigrants who came shut their eyes to the physical ruin and squalor, accepted with love every hardship and tribulation and danger. Thus, in 18 10, the disciples of the Vilna Goan who had just emigrated, wrote:

Truly, how marvelous it is to live in the good country. Truly, how wonderful it is to love our country. Even in her ruin there is none to compare with her, even in her desolation she is unequaled, in her silence there is none like her. Good are her ashes and her stones.

These immigrants of 1810 were yet to suffer unimagined trials. Earthquake, pestilence, and murderous onslaught by marauding brigands were part of the record of their lives. But they were one of the last links in the long chain bridging the gap between the exile of their people and its independence. They or their children lived to see the beginnings of the modern restoration of the country. Some of them lived to meet one of the pioneers of restoration, Sir Moses Monteflore, the Jewish philanthropist from Britain who, through the greater part of the nineteenth century, conceived and pursued a variety of practical plans to resettle the Jews in their homeland. With him began the gray dawn of reconstruction. Some of the children of those immigrants lived to share in the enterprise and purpose and daring that in 1869 moved a group of seven Jews in Jerusalem to emerge from the Old City and set up the first housing project outside its walls. Each of them built a house among the rocks and the jackals in the wilderness that ultimately came to be called Nahlat Shiva (Estate of the Seven). Today it is the heart of downtown Jerusalem, bounded by the Jaffa Road, between Zion Square and the Bank of Israel.

In 1878, another group made its way across the mountains of Judea to set up the first modern Jewish agricultural settlement at Petah Tikva, which thus became the “mother of the settlements.” Eight years earlier, the first modern agricultural school in Palestine had been opened at Mikveh Yisrael near Jaffa. As we see it now – and they in 1810 would not have been surprised, for this was their faith and this was their purpose – the long vigil was coming to an end. But the conception and application of practical modern measures for the Jewish restoration was preceded by a fascinating interlude: Zionist awakening in the Christian world.

The affinity of the Jewish people for Palestine, unique in the historic circumstances, had become an integral part, inextricably entwined in the texture ofWestern culture. It was a commonplace of all education. The persistence of the Jewish people as an entity, kept alive for century after century of monstrous persecution by a faith in ultimate restoration to its Homeland, was congenial to some Christians, unpalatable to others.

The Christian Churches had their share in perpetuating the forced exile of the Jewish people. To Catholics, it was a matter of duty as God’s servants to enforce the Jewish dispersion; they therefore could not even countenance Jewish restoration to their land. It was part of his apostasy that in 464 the Emperor Julian announced his intention of rebuilding the Temple. With the splits and schisms in the Church, the coming of the Reformation, and the evolution of the various Protestant sects, voices were heard proclaiming it as a Christian act to help the Jewish people regain its homeland. Palestine, however, was in the hands of the Ottoman Turks, and there was no means of translating Christian feeling into action.

In practical Christian minds, this situation began rapidly to change during the early nineteenth century.

The first catalytic agent may have been Napoleon Bonaparte. On launching his campaign for the conquest of Palestine in 1799, he promised to restore the country to the Jews. Though Napoleon was forced to withdraw from Palestine, the prospect he opened may have been instrumental in setting off a chain of developments, primarily in Britain, that grew in intensity and significance as the nineteenth century wore on. A distinguished gallery of writers, clerics, journalists, artists, and statesmen accompanied the awakening of the idea of Jewish restoration in Palestine. Lord Lindsay, Lord Shaftesbury (the social reformer who learned Hebrew), Lord Palmerston, Disraeli, Lord Manchester, George Eliot, Holman Hunt, Sir Charles Warren, Hall Caine – all appear among the many who spoke, wrote, organized support, or put forward practical projects by which Britain might help the return of the Jewish people to Palestine. There were some who even urged the British government to by Palestine from the Turks to give it to the Jews to rebuild.

Characteristic of the period were the words of Lord Lindsay: The Jewish race, so wonderfully preserved, may yet have another stage of national existence opened to them, may once more obtain possession of their native land…The soil of “Palestine still enjoys her sabbaths, and only waits for the return of her banished children, and the application of industry, commensurate with her agricultural capabilities, to burst once more into universal luxuriance, and be all that she ever was in the days of Solomon.” In 1845, Sir George Gawler urged, as the remedy for the desolation of the country:

“Replenish the deserted towns and fields of Palestine with the energetic people whose warmest affections are rooted in the soil”

There were times when this concern took on the proportions of a propaganda campaign. In 1839, the Church of Scotland sent two missionaries, Andrew Bonar and Robert Murray M’Cheyne, to report on “the conditions of the Jews in their land.” Their report was widely publicized in Britain, and it was followed by a Memorandum to the Protestant Monarchs of Europe for the restoration of the Jews to Palestine. This memorandum, printed verbatim by the London Times, was the prelude to many months of newspaper projection of the theme that Britain should take action to secure Palestine for the Jews. The Times, in that age the voice of enlightened thought in Britain, urged the Jews simply to take possession of the land. If a Moses became necessary, wrote the paper, one would be found.

Again and again groups and societies were projected or formed to promote the restoration. The proposals and activities of Moses Montefiore found a wide echo throughout Britain. Many Christians associated themselves practically with his plans; others brought forward plans and projects of their own and even took steps to bring them to fruition. What was probably the first forerunner in modern times of the Jewish agricultural revolution in Palestine was the settlement established in 1848 in the Vale of Rephaim by Warder Cresson, the United States Consul in Jerusalem; he was helped by a Jewish – Christian committee formed in Britain for the Jewish settlement of Galilee.

The ideas of Sir George Gawler, a former governor of South Australia, before and after the Crimean War, when he formed the Palestine Colonisation Fund; of Claude Reignier Conder who, with Lieutenant Kitchener, carried out a survey of Palestine and brought to public notice the fact that Palestine could be restored by the Jews to its ancient prosperity; of Laurence Oliphant, the novelist and politician, who worked out a comprehensive plan of restoration and a detailed project for Jewish settlement of Gilead east of the Jordan; of Edward Cazalet, who proposed equally detailed projects – all were broached and propagated against a background of widespread Christian support.

By the middle of the century, the concept of Jewish restoration began to be considered in responsible quarters in Britain as a question of practical international politics. In August 1840, the Times reported that the British government was feeling its way in the direction of Jewish restoration. It added that “a nobleman of the Opposition” (believed to be Lord Ashley, later Lord Shaftesbury) was making his own inquiries to determine:

1. What the Jews thought of the proposed restoration.

2. Whether rich Jews would go to Palestine and invest their capital in agriculture.

3. How soon they would be ready to go.

4. Whether they would go at their own expense, requiring nothing more than assurance of safety to life and property.

5. Whether they would consent to live under the Turkish government, with their rights protected by the five European powers (Britain, France, Russia, Prussia, Austro-Hungary).

Lord Shaftesbury pursued the idea with Prime Minister Palmerston and his successors in the government and was incidentally instrumental in the considerable assistance and protection against oppression that Britain henceforth extended to the Jews already living in Palestine.

The Crimean War and its aftermath pushed the ideas and projects into the background, but they soon came to life again. In 1878, the Eastern Question reached its crisis in the Prusso-Turkish War, and the Congress of Berlin gathered to find a peaceful solution. At once reports spread throughout Europe that Britain’s representatives, Lord Beaconsfield (Benjamin Disraeli) and Lord Salisbury, were proposing as part of the peace plan to declare a protectorate over Syria and Palestine and that Palestine would be restored to the Jews.

Though these reports were unfounded, the idea again caught the imagination of political thinkers in Britain. It was widely supported in the newspapers, which saw it as both a solution to the Jewish problem and a means of eliminating one of the perennial causes of friction between the powers. So popular was the idea with the British public that the weekly Spectator on May 10, 1879, in criticizing Beaconsfield for not having adopted it, wrote:

“If he had freed the Holy Land and restored the Jews, as he might have done instead of pottering about Roumelia and Afghanistan, he would have died Dictator.”

No less significant is the fact that the idea of Jewish restoration, when it was presented in the form of practical projects, was not rejected by the Moslem authorities. In 1831, Palestine was conquered from the Turks byMehemet Ali, who ruled it from Egypt for the next nine years, introducing a comparatively pleasant interlude in the life of the country. It was at this time that Sir Moses Montefiore began developing his practical plans. In 1839, he visited Mehemet Ali in Egypt and put forward a large-scale scheme for Jewish settlement that would regenerate Palestine. Mehemet Ali accepted it. Montefiore was in the midst of discussing practical details with him when Mehemet was forced to withdraw from Palestine, which returned to Turkish rule.

Forty years later, the Turks themselves were presented with practical plans for Jewish colonization and autonomy in a part of Palestine. The most important of these plans was that carefully and conscientiously worked out by Laurence Oliphant, who demonstrated to the Turks that it was in their own interest, as well as in Britain’s, to help fulfill a Jewish restoration in Palestine. His detailed plan for the settlement of Gilead was supported and recommended to the Turkish government by the leading personalities in Britain: The Prime Minister Lord Beaconsfield, the Foreign Secretary Lord Salisbury, and even the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII). The French government, through its Foreign Minister Waddington, also added its encouragement.

The Sultan showed considerable interest in the plan; the Turkish Foreign Office even proposed some amendments for further discussion. But again events intervened. In 1880, a general election drove Beaconsfield – considered by Turkey as her friend – from office, to be replaced by William Ewart Gladstone. To the Turks, Gladstone was an enemy. The Oliphant scheme, based on Turko-British cooperation as well as a similar scheme proposed by the British industrialist Edward Cazalet, were shelved and faded into history. By now the effervescence among the Jewish people began to find its outlets.

Jewish organizations were now launched. The result was a wave of immigration, to be known later as the First Aliyah, which laid the solid foundation of the new Jewish agriculture. The advent of Theodor Herzl was only fifteen years away, and with it the beginning of the modem political frame for the return to Zion: the World Zionist Organization.

Throughout the ages, and now in the nineteenth century, when the restoration of the Jewish people to Palestine and the restoration of Palestine to the Jewish people was discussed in growing intensity, when scores of books and pamphlets and innumerable articles published in Europe, America, and Britain put forward both ideological motivation and practical projects for the consummation of the idea, never once was it suggested openly or covertly that the Holy Land could not, or should not, be restored to the Jews because it had become the property of others. There were many who disliked the Jews; there were Christians who objected on theological grounds to the very idea of reversing the “edict” of exile. Imagine what would happen to the Catholic dogma of the inadmissibility of Jewish restoration if a Jewish state were suddenly to arise! They had enough reason to seek grounds and means of resistance to the spread of the idea. Yet nothing led anyone to believe or to suggest that there was any other nation that had a claim, or had established an affinity or connection, or had made such a contribution in sweat or in blood, to have and to hold the country for its own.

No such nation existed, nor any such claim. The claim of historic association, of historic right, of historic ownership by the Arab people or by a “Palestinian entity” is a fiction fabricated in our own day. After the Jews had been absent as a nation for eighteen centuries, this was a self-evident truth, which is also part of the historic record.

“No nation has been able to establish itself as a nation in Palestine up to this day,” wrote Sir John William Dawson in 1888, “no national union and no national spirit has prevailed there. The motley impoverished tribes which have occupied it have held it as mere tenants at will, temporary landowners, evidently waiting for those entitled to the permanent possession of the soil.”

There was another fact that gave immediate practical impact to the logic and justice of Jewish restoration. Palestine was a virtually empty land. When Jewish independence came to an end in the year 70, the population numbered, at a conservative estimate, some five million people. (By Josephus’ figures, there were nearer seven million.) Even sixty years after the destruction of the Temple, at the outbreak of the revolt led by Bar Kochba in 132, when large numbers had fled or been deported, the Jewish population of the country must have numbered at least three million, according to Dio Cassius’ figures. Seventeen centuries later, when the practical possibility of the return to Zion appeared on the horizon, Palestine was a denuded, derelict, and depopulated country. The writings of travelers who visited Palestine in the late eighteenth and throughout the nineteenth century are filled with descriptions of its emptiness, its desolation. In 1738, Thomas Shaw wrote of the absence of people to till Palestine’s fertile soil.

In 1785, Constantine Francois Volney described the “ruined” and “desolate” country. He had not seen the worst. Pilgrims and travelers continued to report in heartrending terms on its condition. Almost sixty years later, Alexander Keith, recalling Volney’s description, wrote:

“In his day the land had not fully reached its last degree of desolation and depopulation.”

In 1835, Alphonse de Lamartine could write: Outside the gates of Jerusalem we saw indeed no living object, heard no living sound, we found the same void, the same silence…as we should have expected before the entombed gates of Pompeii or Herculaneam…a complete eternal silence reigns in the town, on the highways, in the country… the tomb of a whole people.

Mark Twain, who visited Palestine in 1867, wrote of what he saw as he traveled the length of the country:

Desolate country whose soil is rich enough, but is given over wholly to weeds – a silent mournful expanse. . . . A desolation is here that not even imagination can grace with the pomp of life and action. We reached Tabor safely. We never saw a human being on the whole route.

And again:

There was hardly a tree or a shrub anywhere. Even the olive and the cactus, those fast friends of a worthless soil, had almost deserted the country.

So overwhelming was his impression of an irreversible desolation that he came to the grim conclusion that Palestine would never come to life again. As he was taking his last view of the country, he wrote:

Palestine sits in sackcloth and ashes. Over it broods the spell of a curse that has withered its fields and fettered its energies. Palestine is desolate and unlovely….Palestine is no more of this workday world. It is sacred to poetry and tradition, it is dreamland.

By Volney’s estimates in 1785, there were no more than 200,000 people in the country. In the middle of the nineteenth century, the estimated population for the whole of Palestine was between 50,000 and 100,000 people.

It was the gaping emptiness of the country, the spectacle of ravages and neglect, the absence of a population that might be dispossessed and the growing sense of the country’s having “waited” for the “return of her banished children,” that lent force and practical meaning to the awakening Christian realization that the time had come for Jewish restoration. What is the Arab historical connection with Palestine? What is the source of their fantastic claims?

The Arabs’ homeland is Arabia, the southwestern peninsula of Asia. Its 1,027,000 square miles (2,630,000 square kilometers) embrace the present-day Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Kuwait, Bahrein, Qatar, Trucial Oman on the Persian Gulf, Muscat and Oman, and South Yemen. When in the seventh century, with the birth of the new Islamic religion, the Arabs emerged from the desert with an eye to conquest, they succeeded in establishing an empire that within a century extended over three continents, from the Atlantic Ocean to the border of China. Early in their phenomenal progress, they conquered Palestine from the Byzantines.

Purely Arab rule, exercised from Damascus by the Omayyad dynasty, lasted a little over a century. The Omayyads were overthrown in 750 by their bitter antagonists, the Abbasids, whose two centuries of government was increasingly dominated first by Persians, then by Turks. When the Abbasids were in turn defeated by the Fatimids, the Arabs had long had no part in the government of the empire, either at the center or in the provinces.

But the Arabs had one great lasting success: Throughout a large part of the subjugated territories, Arabic became the dominant language and Islam the predominant religion. (Large scale conversions were not on the whole achieved by force. A major motive in the adoption of Islam by “nonbelievers” was the social and economic discrimination suffered by non-Moslems.) This cultural assimilation made possible the so-called golden age of Arabic culture.

“The invaders from the desert,” writes Professor Philip K. Hitti, the foremost modem Arab historian, “brought with them no tradition of learning, no heritage of culture to the lands they conquered….They sat as pupils at the feet of the peoples they subdued.”

What we therefore call “Arabic civilization” was Arabian neither in its origins and fundamental structure nor in its principal ethnic aspects. The purely Arabic contribution in it was in the linguistic and to a certain extent in the religious fields. Throughout the whole period of the caliphate, the Syrians, the Persians, the Egyptians, and others, as Moslem converts or as Christians or Jews, were the foremost bearers of the torch of enlightenment and learning.

The result was a great volume of translation from the ancient writings of a host of cultures in East and West alike, from Greece to India. Most of the great works in mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy were rendered into Arabic and, in many cases, were thus saved for Europe. The translation period was followed by the even brighter glow of great original works in Arabic on all these subjects as well as on alchemy, pharmacy, and geography.

“But when we speak of ‘Arab medicine’ or ‘Arab philosophy’ or ‘Arab mathematics’,” notes Hitti, “we do not mean the medical science, philosophy or mathematics that are necessarily the product of the Arabian mind or developed by people living in the Arabian peninsula, but that body of knowledge enshrined in books written in the Arabic language by men who flourished chiefly during the caliphate and were themselves Persians, Egyptians or Arabians, Christian, Jewish or Moslem.”

“Indeed, even what we call ‘Arabic literature’ was no more Arabian than the Latin literature of the Middle Ages was Italian…. Even such disciplines as philosophy, linguistics, lexicography and grammar, which were primarily Arabian in origin and spirit and in which the Arabs made their chief original contribution, recruited some of their most distinguished scholars from the non-Arab stock.”

Whatever the precise definitions of the cultural historians, the Arab Empire certainly ushered in a cultural era that illuminated the Middle Ages. In this golden age, Palestine played no part at all. The history books and the literature of the period fail to reveal even a mention of Palestine as the center of any important activity or as providing inspiration or focus for any significant cultural activity of the Arabs or even of the Arabic-speaking people. On the contrary: Anyone seeking higher learning, even in specifically Moslem subjects, was forced to seek it at first in Damascus, later in the centers of Moslem learning in various other countries. The few known Palestinian scholars were born and may have died in Palestine, but they studied and worked in either Egypt or Damascus.

Palestine was never more than an unconsidered backwater of the empire. No great political or cultural center ever arose there to establish a source of Arab, or any other non-Jewish, affinity or attachment. Damascus, Baghdad, Cairo – these were the great, at times glittering, political and cultural centers of the Moslem Empire. Jerusalem, where a Moslem Holy Place was established on the site of the ancient Jewish Temple, never achieved any political or even cultural status. To the Arab rulers and their non-Arab successors, Palestine was a battleground, a corridor, sometimes an outpost, its people a source of taxes and of some manpower for the waging of endless foreign and internecine wars. Nor did a local non-Jewish culture grow. In the early Arab period, immigrants from Arabia were encouraged, and later they were given the Jewish lands. But the population remained an ethnic hodgepodge.

When the Crusaders came to Palestine after 460 years of Arab and non-Arabic Moslem rule, they found an Arabic-speaking population, composed of a dozen races (apart from Jews and Druzes), practicing five versions of Islam and eight of heterodox Christianity.

“With the passing of the Umayyad empire . . . Arabianism fell but Islam continued.” The Persians and the Turks of the Abbasid Empire, the Berbers and the Egyptians of the Fatimid Empire, had no interest at all in the provincial backwater except for what could be squeezed out of it for the imperial exchequer or the imperial army.

To the Mamluks who, in 1250, followed the Crusader Christian interregnum, Palestine had no existence even as a subentity. Its territory was divided administratively, as part of a conquered empire, according to convenience. Its variegated peoples were treated as objects for exploitation, with a mixture of hostility and indifference. Some Arab tribes collaborated with the Mamluks in the numerous internal struggles that marked their rule. But the Arabs had no part or direct influence in the regime. Like all the other inhabitants of the country, they were conquered subjects and were treated accordingly.

Their state did not improve under the Ottoman Turks. The fact of a common Moslem religion did not confer on the Arabs any privileges, let alone any share in government. The Ottomans even replaced Arabic with Turkish as the language of the country. Except for brief periods, the Arab inhabitants of Palestine had cause to dislike their Turkish rulers just one degree less than did the more heavily taxed Jews.

The Arabs did, however, play a significant and specific role in one aspect of Palestine’s life: They contributed effectively to its devastation. Where destruction and ruin were only partly achieved by warring imperial dynasties – by Arab, Turkish, Persians, or Egyptians, by the Crusaders or by invading hordes of Mongols or Kharezmians – it was supplemented by the revolts of local chieftains, by civil strife, by intertribal warfare within the population itself. Always the process was completed by the raids of Arabs – the Bedouins – from the neighboring deserts. These forays (for which there were endemic economic reasons) were known already in the Byzantine era. Over fifteen centuries, they eroded the face of Palestine.

During the latter phase of the Abbasids and in the Fatimid era, Bedouin depredations grew more intense. It was then that Palestine east of the Jordan was laid waste.

Starting in the thirteenth century, with the entry of the Mamluks, all the instruments of ruin were at work almost continuously. The process went on even more colorfully under Ottoman misrule. Bedouin raiders, plundering livestock and destroying crops and plantations, plagued the life of the farmer. Bedouin encampments, dotting the countryside, served as bases for highway attacks on travelers, on caravans carrying merchandise, on pilgrim cavalcades. Count Volney, describing the Palestinian countryside in 1785, wrote:

The peasants are incessantly making inroads on each other’s lands, destroying their corn, durra, sesame and olive-trees, and carrying off their sheep, goats and camels. The Turks, who are everywhere negligent in repressing similar disorders, are the less attentive to them here, since their authority is very precarious; the Bedouin, whose camps occupy the level country, are continually at open hostilities with them, of which the peasants avail themselves to resist their authority or do mischief to each other, according to the blind caprice of their ignorance or the interest of the moment. Hence arises an anarchy, which is still more dreadful than the despotism that prevails elsewhere, while the mutual devastation of the contending parties renders the appearance of this [the Palestinian] part of Syria more wretched than that of any other….This country is indeed more frequently plundered than any other in Syria for, being very proper for cavalry and adjacent to the desert, it lies open to the Arabs.

Neither history books nor reports of travelers, whether Christian, Moslem, or Jewish, report on any other permanent feature of the Arabs’ historical relationship with Palestine. In the tenth century, the Arab writer Ibn Hukal had written:

“Nobody cares about building the country, or concerns himself for its needs.”

This was a mild foretaste of the ruination of a country, carried out over hundreds of years. There is no reason to blame the handful of Arabs who were part of the medley of peoples that made up the settled population of Palestine. They were merely subject residents, usually downtrodden, of this or that village or this or that town. The remote central authority in Constantinople stretched out its conscripting hand to take away their sons, the local tax farmer sucked them dry, the village over the hill, and the rival tribe, had to be guarded against or fought in a cycle of mutually destructive retaliation. The Bedouin nomads tore up their olive trees, destroyed their crops, filled their wells with stones, broke down their cisterns, took away their live-stock – and were sometimes called in as allies to help destroy the next village.

Thus it was that by the middle of the nineteenth century, when hundreds of years of abuse had turned the country into a treeless waste, with a sprinkling of emaciated towns, malaria-ridden swamps in its once-fertile northern valleys, the once-thriving south (Negev) now a desert, the population too had dwindled almost to nothing.

There was never a “Palestinian Arab” nation. To the Arab people as a whole, no such entity as Palestine existed. To those of them who lived in its neighborhood, its lands were a suitable object for plunder and destruction. Those few who lived within its bounds may have had an affinity for their village (and made war on the next village), for their clan (which fought for the right of local tax-gathering), or even for their town. They were not conscious of any relationship to a land, and even the townsmen would have heard of its existence as a land, if they heard of it at all, only from such Jews as they might meet. (Palestine is mentioned only once in the Koran, as the “Holy Land”— holy, that is, to Jews and Christians.)

The feeling of so many nineteenth-century visitors that the country had been waiting for the return of its lawful inhabitants was made the more significant by the shallowness of the Arab imprint on the country. In twelve hundred years of association, they built only a single town, Ramleh, established as the local subprovincial capital in the eighth century. The researchers of nineteenth-century scholars, beginning with the archaeologist Edward Robinson in 1838, revealed that hundreds of place-names of villages and sites, seemingly Arab, were Arabic renderings or translations of ancient Hebrew names, biblical or Talmudic. The Arabs have never even had a name of their own for this country which they claim. “Filastin” is merely the Arab transliteration of “Palestine,” the name the Romans gave the country when they determined to obliterate the “presence” of the Jewish people.

Sir George Adam Smith, author of the Historical Geography of the Holy Land, wrote in 1891:

“The principle of nationality requires their [the Turks’] dispossession. Nor is there any indigenous civilization in Palestine that could take the place of the Turkish except that of the Jews who … have given to Palestine everything it has ever had of value to the world.”

This blunt judgment was entirely normal; it aroused no objections and offended no one. It was a simple statement of a unique and irrefutable fact. The Arabs’ discovery of Palestine came many years later.

We would like to thank ShmuelKatz.com for providing us with the material for this article. This article is republished with the permission of David Isaac, e-Editor of ShmuelKatz.com. For republishing rights please contact David Isaac directly at David_Isaac@ShmuelKatz.com.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

About the author,

Shmuel “Mooki” Katz, born Samuel Katz (9 December 1914 – 9 May 2008) was an Israeli writer, member of the first Knesset, publisher, historian and journalist. He was a member of the first Knesset and is also known for his research on Jewish leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky.

Katz was born in 1914 in South Africa, and in 1930 he joined the Betar movement. In 1936 he immigrated to Mandate Palestine and joined the Irgun. In 1939 he was sent to London by Ze’ev Jabotinsky to speak on issues concerning Palestine. While there he founded the revisionist publication “The Jewish Standard” and was its editor, 1939–1941, and in 1945. In 1946 Katz returned to Mandate Palestine and joined the HQ of the Irgun where he was active in the aspect of foreign relations. He was one of the seven members of the high command of the Irgun, as well as a spokesman of the organization.

In 1948 Katz assisted in the bringing of the ship, Altalena to the shores of Israel. Shmuel Katz was one of the founders of the Herut political party and served as one of its members in the First Knesset. In 1951 he left politics and managed the Karni book publishing firm. He was co-founder of The Land of Israel Movement in 1967, and in 1971 he helped to create Americans for a Safe Israel.

In 1977 Katz became “Adviser to the Prime Minister of Information Abroad” to Menachem Begin. He accompanied Begin on two trips to Washington and was asked to explain some points to President Jimmy Carter. He quit this task on January 5, 1978 because of differences with the Cabinet over peace proposals with Egypt. He refused the high prestige post of UN ambassador. Katz was then active with the Tehiya party for some years and later with Herut – The National Movement after it split away from the ruling Likud. He also has written for the Daily Express and The Jerusalem Post. (source: wikipedia and shmuelkatz.com)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment